Corporate Excess

How GE Violated Its Own Compensation Principles—and How Flawed Policies Led to a Fabled Company’s Long Decline

With all the attention to inequality during the pandemic, I’ve been surprised by how little has been directed at some serial abusers of the “free market.”

Bernie Sanders has railed at billionaires, but most billionaires—corporate founders—have earned their wealth in a competitive market, and so have many of the lesser but still ultrarich, such as athletes and entertainers.

But there is one entitled group that is largely insulated from the market’s judgment—the hired suits who run America’s public companies. These executives have for decades preached the mantra of “pay-for-performance” but they rarely live up to it. They are overpaid when they succeed and—no other word for it—obscenely overpaid for failure.

How do they do it? Intrinsic Value looked in depth at the company once the most valuable and admired in America—General Electric. GE has suffered a terrible and prolonged decline. At the end of 2000, GE was worth about $500 billion. Twenty-one years later, GE is worth barely $100 billion--despite inflation that has eroded the value of the dollar by 60%. And its stock price has crashed from 364 to (at year-end) 94 1/2 —while the S&P 500 index has risen 260%. That is, as the average stock well more than tripled, GE’s shareholders, excluding dividends, lost three quarters of their capital.

Over that time, management repeatedly pledged to “align” the pay of GE’s brass with shareholder results. They devoted oceans of ink to explaining how their compensation practices adhered to the principle of pay-for-performance.

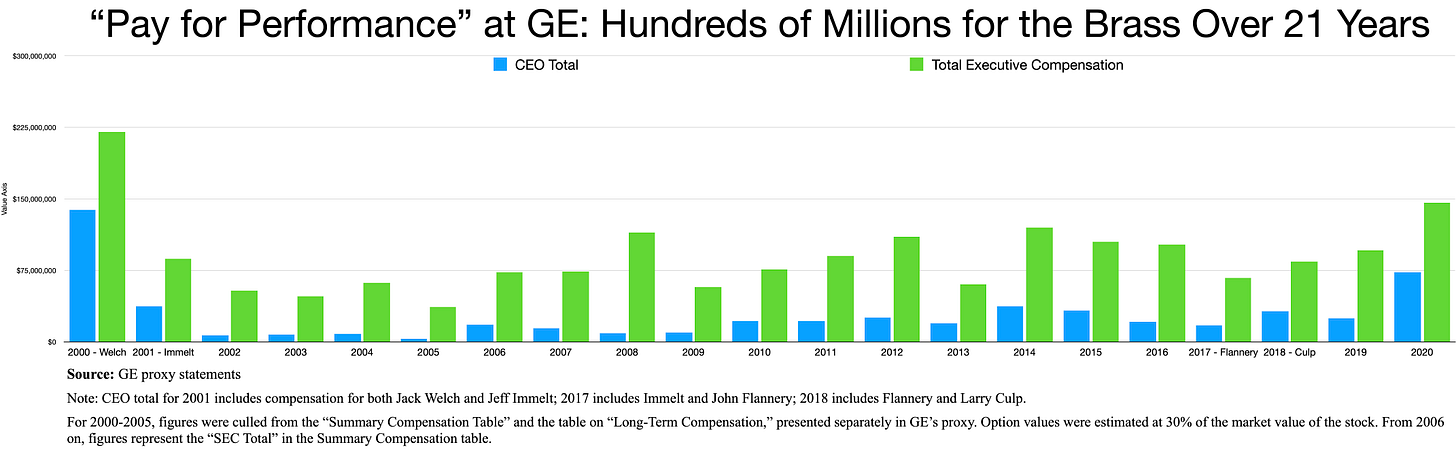

Yet over that span of 21 years, as the shareholders’ investment was disintegrating, GE paid its top five executives an average of $90 million per year. In total, pay to the top five was $1.9 billon. CEOs alone received $594 million—for colossal failure.

Of course, GE’s business results weren’t typical of American industry; they were very much subpar. But the devices employed by GE to endow its executives, and to insulate them from market forces, were all too typical. Their pay plans didn’t noticeably differ from those of other brand-name companies. You can find similar abuses of pay-for-performance at Tesla, Walt Disney, Oracle, American Airlines and many more. At GE the hypocrisy is simply laid bare.

GE has had four chief executives since 2000, a period that spans the last year of Jack Welch, sixteen years of Jeff Immelt, a brief interregnum of John Flannery and, since 2018, Larry Culp. It has hardly remained the same company. Driven by an obsession with deal-making, GE was forever acquiring and divesting, expanding and “transitioning,” which was corporate-speak for unloading the corporate princes acquired in yesteryear that later turned out to be toads. A partial list of the businesses that GE exited, or greatly downsized, include television broadcasting, GE Capital, appliances, water technologies, transportation, industrial solutions, power generation, lighting, and biopharma.

The corporate self-image also evolved. In the Welch years, GE’s proxy statement touted executives for “aggressive leadership.” Recently they have professed humility. And the “4-E” slogan of the Welch era (Energy, Energizing, Edge, Execute) has given way to au courant buzzwords like diversity and sustainable.

But one thing hasn’t changed. GE executives still get hugely rewarded – even when their performance is abysmal. How did they do it? GE didn’t break any rules. Its board devoted extensive thought to compensation policies. They hired the best consultants. And much of their pay was, seemingly, pegged to results.

To understand how the principle of pay-for-performance was subverted into something close to its obverse, you have to understand the cumulative effect of many consecutive annual pay packages any one of which, read in isolation, might appear more or less reasonable. But first, a word on methodology. What is reported here are the SEC-mandated disclosures of pay to the top five “named” executives. Since much of executive pay, at GE and elsewhere, is in the form of stock incentives, the reported figures are rarely equal to what an executive actually pocketed. The figures—compiled from 21 annual proxies by Morgan Goldstein, my dogged and meticulous research assistant--represent the best estimate for the present value of annual compensation when it was awarded. That remains the SEC’s standard.

One thing clear in the proxies is that GE has long paid lip service to “aligning” pay to performance.

In 2003 (after a year in which the stock fell 39%, notwithstanding which Immelt’s compensation totaled $15.6 million, and the named executives $54 million), GE asserted “We are also taking steps to link his pay more closely to company performance.” In 2005 it repeated that Immelt’s pay would be focused “entirely” on “incentives for performance and alignment with investors.”

It reiterated the message often. The 2017 proxy, reporting on Immelt’s $21 million-haul, featured a jazzy, three-color chart entitled “Aligning Pay with Performance.”

The next year—by which time Immelt had been cashiered—GE, apparently concluding that the prior alignment had been unsatisfactory, took steps to “increase accountability and alignment with investors.” The 2020 proxy mentioned “align” or “aligning” 68 times. The 2021 proxy reported that the compensation committee of the board would act “to increase management accountability and more closely align management’s interest with shareholders”—implying that despite GE’s 20-year-long insistence that it was aligning pay with performance, it had not succeeded.

Despite its expression of principle, GE was unwilling to live by the implications of pay-for-performance, which would have compelled mediocre executives to forgo seven- or eight-figure annual bonanzas and subsist on merely ordinary high annual incomes.

It averted the substance of pay-for-performance in various ways. One was changing the bar, the hurdle measured to rate “performance.”

The comp committee repeatedly made special allowance for hard times, such as a recession or market slump. In 2002, in justifying Immelt’s pay, the proxy noted the “unusually challenging global economic environment.” In 2003, it revised its assessment of the difficulty upward—now the environment was deemed to be “extraordinarily” challenging. So again in 2010 and 2017.

This contradicted the principle of “alignment.” No one gave the shareholders a bonus when the stock was down.

And its application was one-sided. The comp committee certainly didn’t dock executive pay when times were good (and presumably, corporate profits came easier).

Another device was selective use of performance metrics. The 2006 proxy, explaining the CEO’s pay, cited GE’s return on capital of 16%. Return on capital is the single most important measure of performance, and 16% is an impressive rate.

However, in subsequent years, when the return fell, GE stressed an alternate metric: how its earnings ranked in size, compared to earnings of other companies in the S&P 500. Size is not important. What matters to investors is the rate of return on their investment, not whether they are part of some gilded empire.

Similarly, the comp committee made selective use of stock returns. Commenting on the CEO’s $33 million payday for 2015, the proxy asserted, “Mr. Immelt performed extremely well in 2015… as evidenced by GE’s TSR” (total shareholder return). GE stock indeed outperformed that year. But it underperformed for most of the decade. The next year’s assessment of Immelt omitted mention of stock performance; it simply observed that he performed well in, yes, “a challenging environment.”

Had more investors read the proxy, they would have found it remarkably transparent that pre-set hurdles were adjusted, presumably, to elicit a more favorable result. Some proxies helpfully detailed, “how the compensation committee adjusted performance metrics.”

GE said repeatedly it did not rely on rigid formulas; setting pay was art as well as science. While some flexibility is fine, the board abused its license by relying on soft metrics when hard ones delivered unwanted news. In good years the stock price mattered, in others it was a qualitative factor such as increasing GE’s “use of technology to create value for our customers” (2002) or spending more on research and development (2010), or “executing” on a debt exchange and “launching a plan” (2016) to sell financial service businesses. This is not “alignment,” because shareholders aren’t rewarded when the executives launch a plan. Launching plans is what they do; it’s part of the job. They are supposed to be rewarded for success.

The overall flaw was pervasive short-termism. Incentive pay was conditioned on improving yearly performance or over three-year stretches. The financial press wrote up each year’s pay package, duly reporting that a large share of pay was, in GE’s words, “at risk.”

GE Stock Does a Long Goodbye, 2000-2021

But the overall effect could be seen only when a long stretch of proxies were reviewed as a group. A small problem, in GE’s case, is that the guaranteed portion of pay was so high that even if a higher proportion was “at risk,” the executive’s fortune was assured. Immelt’s salary was usually above $3 million; in addition, his bonus was at least $4 million for all but three of 15 years running—and this was before his stock awards, options, pension awards, and “all other” compensation.

A larger problem was that the time periods for vesting awards was too short. A CEO can often can goose reported earnings, or generate enthusiasm for the stock, for a while. Indeed, Welch boasted of it. He was celebrated for “managing earnings,” a casual and routine deception to give reported earnings an unwarranted appearance of steady and rising predictability. Real life is bumpy.

The greatest problem was that new performance targets were set every three years, and sometimes more often. Therefore, after a down period, executives were rewarded merely for returning the company back to where it had been. Think of a baseball manager who loses eight of his first ten games. Do you give him a bonus for getting the team back to .500? It repeatedly happened at GE.

Since each incentive was potentially very large, it hardly mattered that in some years the incentive was never cashed. You only need to get rich once, and sooner or later, the bar will be set low enough. CEO compensation was higher than $15 million in 14 of the 21 years, and in half of those, it was at least $25 million. Executives were essentially guaranteed to get very rich even though, and even while, the shareholders were losing their shirts.

A flaw particular to GE, as I wrote in 2017, was the delusion that deal-making was, per se, an accretive activity (this is a legacy influence of the hyperkinetic Welch, who also boasted of canning 10% of his workers every year). Frenetic asset turnover seriously distorted GE’s compensation, because almost every deal, when it is struck, looks good. Whether it is good is often unclear until later. The proxy lauded Immelt for meticulously unloading many of the businesses for which, previously, Welch had been praised for acquiring. But not every deal is value-enhancing (otherwise, the party on the other side would not be so willing). In 2015, Immelt paid more than $10 billion for the gas and steam turbine business of the French power company Alstom. CNBC market commentator Jim Cramer, a reliable barometer of Wall Street sentiment, hailed it as GE’s “best deal in a century.” Explaining how it allocated the bonus pool for that year, the GE proxy congratulated Immelt and other named executives for completing the “largest portfolio shift” in GE history.

True pay-for-performance would reward executives not for ‘shifting the portfolio’ but for contributing to results. Alstom never did. Within a few years, the power company turned out to be GE’s worst deal ever. It led to massive losses and a $22 billion write-off. This suggests the true cost of GE’s compensation system. Generations of executives were motivated to seek short-term returns at the expense of long-term value.

The board undercut its supposed commitment to alignment by selectively breaking its own rules. It made much of the fact that from 2003 on it ceased awarding stock options to the CEO (who did, however, receive performance shares, a rough equivalent).

However, in 2010, GE noted that some of Immelt’s performance shares had been cancelled because, in fact, the company had not performed. It simultaneously awarded him a mammoth, two-million stock option grant. Having failed to clear the agreed-upon hurdle, he was presented with another. Immelt, by then, had been CEO eight and a half years. The stock over that span had plummeted 60%. The options would enable him to profit merely for recouping prior losses.

In 2017, Immelt was succeeded by John Flannery. Flannery lasted 14 months. Larry Culp became CEO in October 2018—the first outsider to run GE (he had been a director for some months prior and, before that, CEO of Danaher). GE’s contract gave him large incentives. He was guaranteed an annual grant of performance shares—equity dependent on performance—worth $15 million on a present value basis. He was also given a lucrative “inducement grant” to take the job, payable if and as the stock appreciated. Potentially his contract was worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Jim Cramer called it “the best performance-oriented contract I’ve ever seen.” This writer called it “the expensive lesson GE never learns.”

One worrisome sign was that Culp’s contract secured his services for, and conditioned his incentives on showing improvements within, four years—a rather short haul considering the likely difficulty of turning around a behemoth that was clearly troubled. Another was that the board seemed dazzled by the employee whose role it was to oversee. The comp committee and the board variously referred to Culp as a “highly successful” CEO with a “proven track record” although, of course, all the proof had occurred at his previous employer. In the past, GE’s board had prided itself on not providing executives with severance or change-of-control agreements. As the 2010 proxy noted, “They [the executives] serve at the will of the Board.” Culp’s contract included $4.6 million for termination and $100 million for change of control.

Moreover, his large incentive was conditioned on the most fleeting measure of success—raising the average stock price over thirty days. The first proxy in the Culp era asserted, “We foster shareowner alignment”—but most “owners” are willing to stick with a stock for more than thirty days.

Reporting on 2019, Culp’s first full year, the proxy praised Culp for selling various units and reducing GE’s debt. It claimed “significant progress” but candidly added, “we have more work to do on many fronts.” Culp was paid $24.6 million.

When the pandemic struck, GE’s stock collapsed with the market, but its subsequent recovery was muted. After years of losses, GE was profitable in 2020, but at a depressed rate. Culp became convinced that GE’s recovery would take longer than anticipated. Suddenly, his contract (conditioned on four-year performance) didn’t look so good. The board began to fret that he might leave with the job incomplete.

Paying extra to “retain” a CEO, above their extraordinary normal compensation, is common practice, as if CEOs suffered from a rare motivational deficit. That had not been the approach at GE. Running a great industrial enterprise was thought to be motivation enough, so the comp committee had reckoned in 2005 when it declaimed, “The CEO of GE needs no retention compensation.” But Culp was different, particularly as the share price, against which his future payout would be determined, plunged. The board met with large investors, postulating that something had to be done to keep the apparently restless Mr. Culp in the saddle. Reaction was negative. The investors had, as the proxy delicately reported, “concerns” about granting “large equity awards to the CEO and CFO, at lower stock price targets than the CEO’s original inducement award,” and further concerns that executive pay was “misaligned” with multiyear share performance.

In August 2020, the board amended Culp’s contract, bestowing on him a “Leadership Performance Share Award” that lowered the benchmark against which his progress would be measured to the then-much reduced share price of $53. Culp still stood to reap a fortune for scoring corporate touchdowns, but the goalpost had been moved significantly closer, the prior distance now being considered too difficult in light of the “unprecedented challenges” faced by the beleaguered Mr. Culp. As a first installment, Culp would receive $47 million should the stock recover to $80 (rather than, as before, to $149). The new target was actually below where the stock had stood when Culp was hired. And Culp would need to hit the target for only thirty days. Later in 2020, with most shareholders still wallowing in losses, the $47 million was his.

The board asked shareholders to support Culp’s amended pay package, which potentially was worth upwards of $230 million. Updating its prior refrain, the board said the pay-for-performance “culture” was, now, “fully embedded in GE at this juncture.” A majority of GE shareholders rejected Culp’s package, although the SEC-mandated “say on pay” vote was non-binding; it cost Culp nothing.

GE also reported that Culp had “voluntarily” forfeited his bonus, an unctuous admission in light of Culp’s total compensation for 2020 of $73 million—1,357 times the median GE employee’s pay—and especially in light of its suggestion that the great man’s compensation should be left to his personal virtue, to his magnanimous character. It is the board’s responsibility to withhold bonus when it deems proper, not to meekly await an act of charity from an executive it oversees.

It needs only to be added what the board received for rewriting, in the midst of a terrible pandemic and severe business distress, Culp’s employment contract: two more years of his services. The amendment was the corporate version of a stickup.

GE has lately announced plans to split the century-old firm into separate entities focused on aviation, health care, and energy, a tacit admission that the old GE has failed. If only as a model that those companies should not emulate, it is worth pondering the values implied but not fulfilled in Culp’s “leadership” award. Surely a corporate leader would feel an alignment with his shareholders, who had trusted their capital to him. Surely he would seek to reasonably align his prospects with those of employees working through a pandemic and through repeated rounds of layoffs. Surely, in a crisis, a leader would voluntarily seek to work harder and longer to see through the job that, at an enormous level of pay, he had pledged to undertake. This GE, and its craven board, conferred an entitlement that violated any common notion of leadership. The new baby GE’s would do well to remember the unhappy lesson of their parent, now stretched over twenty years: companies that pay outsized rewards for short-term success in the long-term are likely to achieve neither.

Pre-Order Ways and Means

My new book, Ways and Means: Lincoln and His Cabinet and the Financing of the Civil War, will be published by Penguin Press in March 2022.

You can preorder Ways and Means here:

Bravo, Roger!

GE is not alone. This occurs across most public companies. Part of the delta between what private equity companies return ~17% and public companies ~10-11%.