Dateline: Caracas

Venezuela’s Democratic Roots Deeper Than Trump Knows (or Cares)

Most literate Americans know that Venezuela had a nasty dictator, Nicolas Maduro, whom the U.S. captured, and that it has a lot of oil and probably gangs and drugs. They may not know much more.

Ignorance helps to explain the relative apathy shown by Americans toward the savageness of the Maduro regime, which translates to apathy toward the 30 million Venezuelans who have suffered under him.

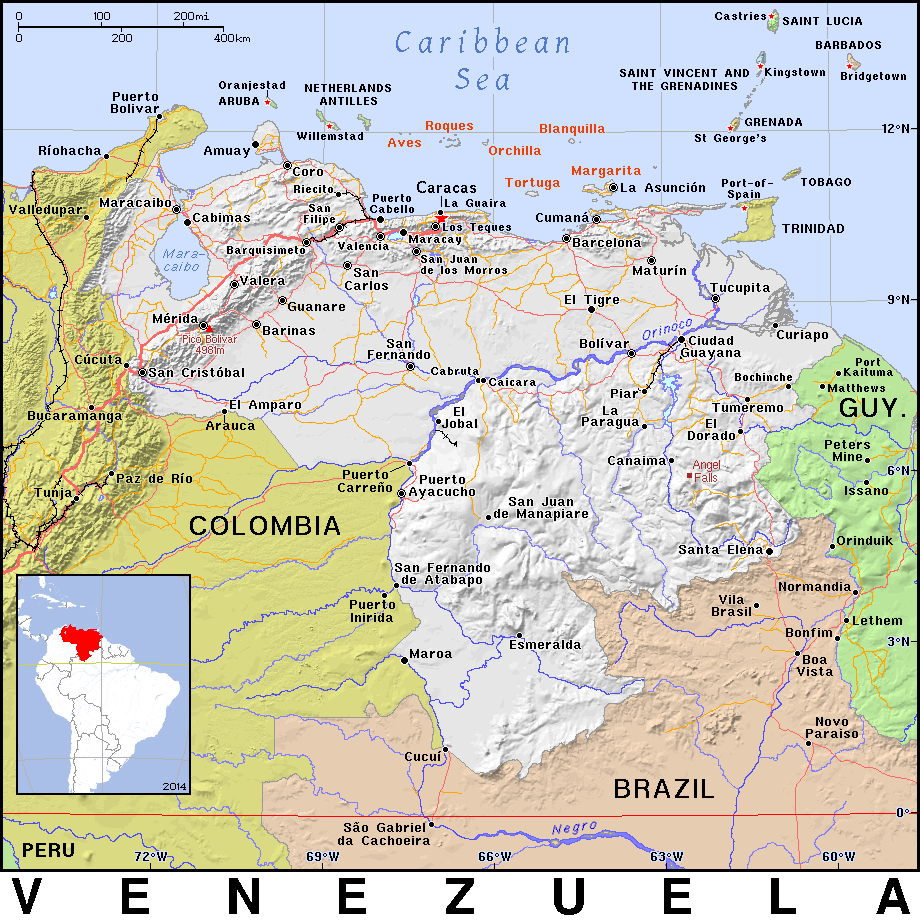

When I returned from a two-year hitch in Caracas at the end of the 1970s, a relative asked me how I had fared in “Argentina,” whose capital is as close to Caracas as Washington, D.C. is to Kazakhstan.

Venezuela then—unlike Argentina—was a vibrant democracy. The people had acquired the presumption of electoral participation and the expectation of peaceful transition.

From 1958 (when a military regime collapsed) into the early 2000s, voters went to the polls every five years and often dislodged the ruling party.

During the 1978 presidential campaign, which I covered for the Caracas Daily Journal, an English-language newspaper, I saw raucous street rallies and energetic campaigning that mimicked the electoral enthusiasm of a somewhat earlier era in America. Public interest was intense, and the culture had absorbed many of our democratic norms.

Among educated Americans, it was a common supposition that Latin Americans resented the U.S., but as an American in Caracas I didn’t experience that. Venezuelan reporters—my colleagues—were ever helpful and intensely interested in what Americans thought of the country, especially its political process.

One time, a reporter asked me which of the most prominent left-wing parties, one known by the Spanish acronym “MIR,” the other as “MAS,” Americans “feared the most.” I gave the only honest answer that wouldn’t hurt his feelings: “about the same.”

I also free-lanced stories to American papers, including the Wall Street Journal. Although these stores contained little that was new to a Venezuelan audience, the Venezuelan papers reported on my stories as though they were big news. Just the fact that the gringos were noticing was significant.

Venezuela’s relationship toward America had been caricatured as hostile when a mob attacked Vice President Richard Nixon’s motorcade in Caracas in 1958. The caricature had to be revised three years later, when Jacqueline Kennedy (who addressed the locals in Spanish) was enthusiastically cheered.

The ambivalence was expressed in the title of a book by the Venezuelan journalist, Carlos Rangel, The Latin Americans: Their Love-Hate Relationship with The United States.

In between Nixon’s visit and mine, democracy had established roots, the State had nationalized the oil industry, previously run by foreign concessionaires, and anti-Americanism had faded.

The “love-hate” existed, but it was the love-hate of a younger sibling toward an older sibling. That may sound patronizing, but we were the more established democracy, and more powerful and prosperous. What Venezuelans wanted most from the United States was its attention, if not admiration.

Venezuelan reporter friends routinely kidded me by calling me “Cia”, telegraphing a common hunch that my actual employer was the Central Intelligence Agency. Underneath the joke lay a serious belief that America stood ready to intervene if things went sour—that is, veered left.

Another version of the “CIA” myth was that my paper, published by the American journalist Jules Waldman (who started me at $100 a week) served as a tool of the U.S. State Department.

As an American voice, the “D.J.,” as the paper was known, was careful not to get in front on sensitive stories. The night of the election, the Social Christian candidate (who had been guided by the American media consultant David Garth) held a decisive lead over the incumbent Social Democrats.

The Venezuelan papers reported that the challenger had won. In the absence of an official tally, the D.J. refused to declare a victor. I was furious, but my superiors thought it unwise for an American paper to be calling a change of power.

The two main parties were centrist in the terms of the day. Each favored a welfare state and a hefty government presence but were comfortingly pro-American and anti-Communist.

Violent leftist groups had tried to overthrow the democracy in the 1960s, but the government crushed them. Some of their former leaders traded in their fatigues and ran for office, but extremism held no purchase with the people, and the center held. By the ‘70s, oil wealth was flowing and Venezuela passed for stable.

On my first flight to Venezuela, a local beer executive told me to expect “the Texas of Latin America.” He meant a country with a sunny disposition, unashamed to wear its wealth, steeped in oil. Venezuelans enjoyed having a good time; I was not to expect ancient Athens.

Its democracy was not perfect. The government paid off many members of the local (and also some of the foreign) press. The executive, although freely elected, was all-powerful. Congress was largely a sham.

When I lived in Caracas, OPEC (of which Venezuela had been a founder) was flexing its muscles, and the government’s oil revenue soared, presenting a problem akin to that of the fabled poor family that wins a lottery.

Corruption, payoffs to politicians, and waste were conspicuous. One time, an official was treating a group of foreign journalists to rounds of imported Scotch.

“Who’s paying for all this?” I inquired.

The official smiled sadly. “There is plenty of oil.”

You can hardly blame the public for becoming cynical. Another time, I was trying to understand an oration in the palm-shaded Congress for some ambitious if wholly impractical government proposal.

“What is he saying?” I demanded of an older Venezuelan colleague in the press gallery, who was taking down every word.

“Pura mentira” (pure lie), he noted.

The most serious problem of Venezuelan democracy was one common to democracies. The government used its wealth to buy popular support with subsidized goods, such as gasoline and food products.

People who had been farmers migrated to cities. Despite its vast arable territory, Venezuela gradually became dependent on food imports—paid for with oil exports.

A short answer for how successive elected governments failed is that they failed to heed the counsel of the architect of Venezuela’s state oil industry (and of OPEC), Juan Pablo Perez Alfonzo, to “sow the oil” in productive industry. Too much was squandered.

When the price of oil cracked in the 1980s, Venezuela no longer had the revenue to sustain the illusion of middle-class prosperity. Public cynicism curdled into bitter discontent.

In 1992, Venezuela suffered a pair of January 6 moments. A charismatic former tank commander, Lieutenant Colonel Hugo Chavez, attempted a coup, and though he was captured and jailed, younger army officers acting on Chavez’s behalf tried again.

Although the coups failed, economic hardship created a groundswell of support. In 1998, Chavez ran for President as an anti-establishment populist. He shocked the establishment and won.

Chavez governed as a repressive leftwing autocrat. When Chavez died in 2013, he was succeeded by his vice-president, Maduro, who was both more brutal and more incompetent.

In the United States, during the “Great Recession” of 2007-’09, gross domestic product fell about 4%. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, peak to trough, GDP fell 30%. In Maduro’s Venezuela, economic output fell 68%. The currency has collapsed and all vestiges of democracy have disappeared. Some 7 million Venezuelans are estimated to have fled. (Among them is the writer Ariana Neumann, whose late father, Hans, a refugee from Nazi Europe, had owned the Daily Journal. Under Chavez, the paper folded.)

A Venezuelan friend of a friend, living in Spain, spoke hopefully of Maduro’s removal as a necessary first step. This expat, a former model, said, “I think of it [the Maduro reign] as an unsightly cancer on my face. The doctors have just taken it off, but that’s not the end; it’s the beginning. It leaves a scar, a long, painful course of treatment has to take place.”

Since seizing Maduro, President Trump has said much about Venezuelan oil and little about democracy, except that he does not think Venezuela is ready for it.

When the Berlin Wall fell, no one suggested that Poland wasn’t ready for democracy, even though no living Pole had ever cast a free ballot.

Democracy requires will and repeated practice. You don’t get more ready by waiting. Vaclav Havel’s only preparation was a jail cell.

As noted, Venezuela has a rich living memory of democratic experience. Most recently, the public showed courage and commitment. In 2024, Maduro barred the popular opposition candidate, Maria Corina Machado, from running. Ten million dared to go to the polls. Tally sheets collected by poll watchers indicated a two-to-one victory for Machado’s stand-in.

The Maduro government did not release official results and Maduro declared himself the winner. The only plausible conclusion is: he stole it.

Trump has casually dismissed the leadership qualifications of Machado, maybe because she has won the Nobel Peace Prize that Trump craves and also, I’d argue, because Machado, who until recently had been in hiding, has principles and guts. She could command popular support and therefore would not need the support of Trump.

Even worse, Trump has shown the fawning eagerness to deal with Maduro’s successor that he often exhibits toward autocrats. Delcy Rodríguez, the former vice-president, was a central part of the repressive Maduro government. Extremism is in her blood. In 1976, her father, a leftwing guerilla fighter, was involved in the kidnapping of William F. Niehous, a U.S. executive at Owens-Illinois, a glass manufacturer. (Neihous was rescued three years later.) Rodriguez’s father died in a government prison, reportedly tortured. Delcy Rodriguez has called the Chavez-Maduro revolution “revenge for the death of our father.”

A cynic would suspect that Trump is happy to deal with Rodriguez because she is unburdened by democratic values and because, since she lacks a popular mandate, she would have more to gain by dealing with President Trump. Perhaps such a deal would involve granting oil leases to American concessionaires friendly to Trump and granting an extended lease on power to Delcy Rodriguez.

It doesn’t matter who President Trump supports; the choice of Venezuela’s leader must be up to Venezuelans. I am glad that Trump deposed of Maduro and glad that the U.S. military performed their job with skill, but as my friend’s friend says, the road back is long and hard. It must begin now, with a transitional ruling council including Machado, and with a specific timetable for scheduling elections.

Given Trump’s disinterest, oppositionists in Venezuela may have to own their future by taking to the streets. Machado would be advised, despite the risks, to return to Venezuela and hazard a public role.

The U.S. attack will be unjustifiable if its result is merely mercantile. Venezuelans—like the entire free world—once put great faith in the American ideal. Ignoring the people’s wish for democracy, which they have earned, would be a terrible betrayal.

Great piece, Roger--as usual. Given the utterly supine state of the Republicans, who control our Congress, pushback from the Venezuelan opposition is the only way to counter Trump's imperialism.

Good piece, Roger. I remember those days well. There's nothing more condescending than people who've never had to endure a dictatorship patronizing those who did by questioning if they are ready for democracy.