Democrats have their work cut out for them. Donald Trump’s hunger to remake the federal government and his in-some-instances offensive cabinet selections will tend to push the party into its natural corner: reactive and oppositional.

The party can assume its well-worn cloak as Trump’s magnetic opposite, the same suit it has worn for the past eight years.

But merely being not Trump, or being against him, fails two necessary tests. It fails politically, as Kamala Harris can attest. And it fails to address, or even acknowledge, that Democrats no longer espouse a coherent and sensible body of polices for what most Americans want.

Losing does breed opportunity, but to exploit it Democrats have to look honestly at where they went wrong. It is more profound than campaign tactics or messaging.

The root of their trouble is basic to what the party has become: hidebound by a set of ideological biases and a nodding habit of groupthink. Perhaps one issue in a generation can be treated as a moral challenge, beyond the realm of reasonable debate (though even Abraham Lincoln, who faced a truly moral test, recognized that “There are few things wholly evil, or wholly good.”)

When a party treats every issue as a once-in-a-generation crisis it backs away from the habit of political give-and-take. It loses sight—as Democrats did--that most political issues involve tradeoffs.

Democrats in recent years have become a party of moral absolutists--on climate, on covid, on identity politics, of slavish rejection of school choice and, among other issues, on economics, promoting a worldview bizarrely suspicious of capitalism and insensible to reasonable restraints on spending. (Yep, Trump promises potentially bigger deficits, but he isn’t the Democrats’ problem.) Liberals in the distant era of Bill Clinton focused on reducing deficits and inflation to stimulate investment and growth. They succeeded. Party doctrine today narrows every economic question to its effect on inequality, framing business not as a remarkable engine of prosperity but as a presumptive evil. Remember those 2020 primaries, one candidate after another excoriating Big Oil, Big Pharma, Big Tech, Big insurance, big whatever?

Joe Biden, who had been an economic moderate for forty years, as President governed as a doctrinaire interventionist, distorting the mission of the SEC for climate goals, tilting the FTC against business on the basis of novel antirust theories (mostly shot down by the courts), demonizing plain vanilla capital transactions (i.e., share buybacks) and overtly tilting the scales to favor unions. The President repeatedly attempted—despite the objection of the Supreme Court—to forgive billions of student debt, that is, he attempted to give away vast sums of public money to borrowers of above-average means, on the unsupported premise that it would lessen inequality.

Americans want a safety net for those left behind, and reasonable regulation is a cornerstone of American success. But why is it that Democrats shy from pointing out that private enterprise provides the wealth that not only fuels prosperity but also funds the government as well as philanthropy and NGOs? Has it not occurred to them that most Americans aspiringly work in the private sector?

The political problem with an ideological approach is not that absolutist positions are necessarily wrong but that its mindset breeds rigidity, an unappealing narrowness. After the George Floyd murder, most Americans were horrified, but they were also upset by the looting and rioting that followed. Democrats were so conditioned to the idea of racism as the defining evil that they could not acknowledge that protests against racism had incited unjustifiable mayhem and created new victims. The ideological purity of the party’s response troubled people, across the ethnic spectrum, who frowned on looting even as they frowned on a police killing.

The party reflex of treating policy questions as moral tests reached a crescendo during covid. Although so much about the pandemic was unknown, Democrats oozed a certainty that they knew best and that dissenters were bumpkins recklessly endangering the public health.

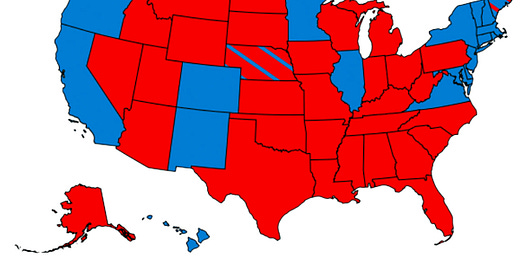

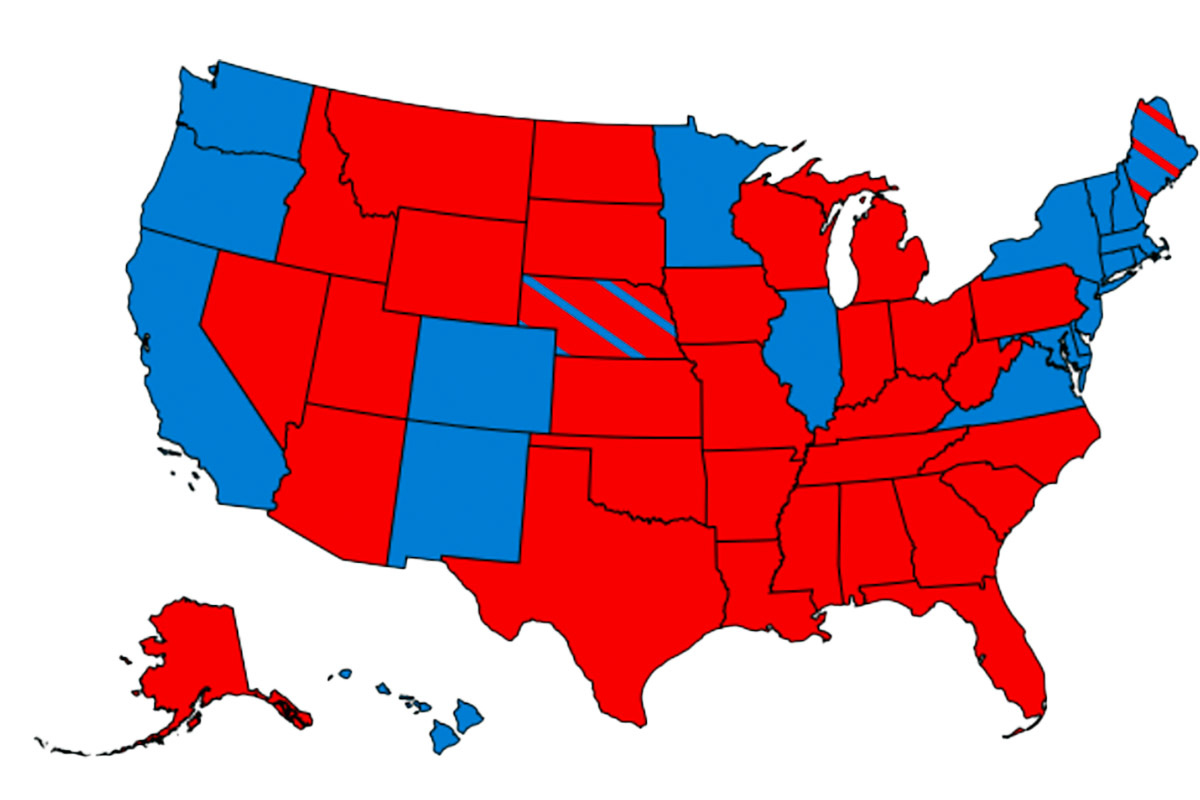

During the pandemic’s first year, when, according to the CDC, mortality was appreciably lower in Republican Florida than in liberal California, the party’s moral stewards wagged unlovely fingers at those who presumed to question even extreme or illogical-seeming measures, even, in my home state of Massachusetts, requiring cyclists to wear masks. (To be clear, there was no discernible political pattern; the map did not suggest a blue-red correlation either way.) Democrats were right in pushing for vaccines, but they failed to acknowledge that health restrictions also involve tradeoffs. Their too-ready mantra, “Follow the science,” became an excuse for not thinking about which measures, such as vaccines, achieved the most benefit for the least cost. Refusal to think in terms of tradeoffs led to prolonged and unforgivable school closures, which caused enduring learning loss and perhaps psychological harm to kids.

Balancing tradeoffs is the singular burden on democratic government. To analogize, it would be easy to cure the banking system of irresponsible loans, or inequities in loan-making. Simply close the banks. Minimizing bad lending while continuing to have banks, so that people can get mortgages and car loans, requires balancing competing interests, which is what government is supposed to do.

Democrats have similarly resorted to a curiosity-crushing slogan, “It’s a settled science,” on climate. They aim to blot out discussion of how, and how rapidly, society ought to transition to green energy, which depends on policy tradeoffs as much as science. Curbs on fossil fuels impose costs as well as presumptive future benefits—for instance, limiting liquified natural gas exports reduces a major source of U.S. exports and strengthens the demand for LNG from Russia, and without adding to the supply of non-fossil alternatives. Perhaps President Biden did weigh such arguments when he imposed a moratorium on new LNG exports, but the White House language—”the existential threat of our time … urgency demands” was the language of absolutism.

Similarly, candidate Harris’s cancellation of her previous support of a ban on fracking didn’t persuade voters because she offered no rationale for flipping the switch. She failed to couple her reversal with some recognition that promoting cheap energy (also a Democratic priority) was in conflict with restricting drilling. Had she acknowledged the tradeoffs—something like, “We have to balance the goal of decarbonizing with the cost to consumers and to the U.S. economy, given the limits of how much decarbonization the U.S. can achieve on its own”—she would have sounded thoughtful and real. But that would have violated the party narrative that brooks no challenge to the notion of a single “existential threat.”

It’s worth noting (because the phrase is heard so often) that “follow the science” imposes an intellectual straitjacket that is less scientific than it sounds. Science is a process as much as a conclusion. The scientific method is hypothesis, experimentation, observation: new hypothesis. Religion describes a fixed body of belief; science evolves. The addition of the definite article—“the science”—seeks to imbue science with the fixity of faith.

That does not mean that nothing is settled. To take an easy case, RFK, Jr. has been wrong on vaccines causing autism and irresponsibly wrong in confusing the covid vaccine as the cause of illness rather than a life-saving preventative. And he is wrong to demonize, with a broad brush, the pharmaceutical industry or the agrifood complex—respectively, they produce life-saving drugs and have fed millions of previously hungry people.

But he is right about the unhealthfulness of processed foods, and the utter foolishness of subsidizing corn syrup, and he makes a plausible case that America is overmedicalized. And he senses a popular discomfort with authority that Democrats might be slower to reject, even as they discard his conspiracy theories.

At his most dangerous, RFK reflects the anti-expert strain of American politics, a close cousin of the “paranoid style” dissected by the late historian Richard Hofstadter. It is not to be taken lightly. The historical trail from Tulsi Gabbard, who blamed NATO for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, leads directly to 9-11 deniers to JFK conspiracy cultists to Joseph R. McCarthy. In a complex society, expertise is necessary. Leading the Pentagon or the Federal Reserve require expertise. Some issues are so complex or counter-intuitive that popular or reflexive judgments are likely to be wrong. Sugar additives may taste good but are not good for you. (Nutritionists know better.) Non-experts tend to favor trade barriers though—as in Trump’s first term—they result in retaliatory barriers against American products and on balance make us poorer.

Democrats do not lack for experts but they have, I think, erred in the opposite direction, at times evincing a respect for expertise that borders on reverence. Anthony Fauci was hardly the public enemy that some Republicans claimed, but neither was he entitled to uncritical obedience. George Bernard Shaw observed that every profession is a conspiracy against the laity. There is a strain in the Democrats of priests on high advocating for what they presume to be the interests of the masses—but not hearing the masses. They refused to consider that they were wrong on inflation, grocery prices be damned, and they were wrong on the 2024 election. So strange for a party obsessed with preserving democracy, the leadership repeatedly sought to insulate the nominating process from popular input. First, President Biden’s minions sought to delay the New Hampshire primary (where he had won zero delegates in 2020). Then, party leaders imposed a virtual cone of silence around Rep. Dean Phillips, who challenged Biden in the primaries, as if challenging an incumbent were a sort of party treason. When questions about the President’s fitness arose, leadership and supportive press sought to squelch them as being Republican-inspired distortions. And when Biden stepped aside, the party anointed Harris without a single primary or even a straw poll. What was missing from the entire process was any public voice.

Note the difference between now and 1968, when the President, Lyndon B. Johnson, suddenly quit the race. The vice president, Hubert Humphrey, faced stiff opposition in primaries, and might well have lost the nomination had not Robert F. Kennedy (the current RFK’s father) been murdered.

To Democrats who recall the ‘60s, when a parade of Presidential advisors and generals were unmasked for stretching the truth (or lying) about Vietnam, the elevation of experts into high priests is discordant and off-putting. Sixties Democrats had generally the same values as today’s—sympathy with the little guy, moral abhorrence of race prejudice, a belief that government could effect positive change—but their spirit was raucous and rebellious. Disabused by the war, turned off by a materialism that struck younger idealists as empty, they trusted no one (no one over 30 at any rate). If today’s Democrats live in fear of a counter narrative, in the ‘60s the party was all counternarrative. Rather than cower at the establishment, two insurgent senators, the offbeat, poetry-writing Eugene McCarthy and RFK, challenged the sitting President of their own party and brought him down. The party was buoyant not timid, free-wheeling rather than regimented, outspoken rather than correct.

Democrats today could do worse than to mime some of that open spirit. Get used to less conformity and more genuine diversity, let all voices speak, stop worrying about who used what word and triggered which offense. Sunlight is indeed the best disinfectant.

Democrats have at least two years in the political wilderness. They can use that period to advantage by being pragmatic critics and members of the loyal opposition as distinct from being oppositional.

Work to make the Trump Administration better than it would be; when possible, negotiate to improve Republican policies in return for a bipartisan stamp. A good case could be Social Security, which will be unable to make full payments in only ten years.

Although both parties promise to protect this signature legacy of the New Deal, neither wants, on its own, to legislate a fix—which would involve politically unpopular tax hikes and/or benefit cuts. A small bipartisan commission—how about Gina Raimondo, Jamie Dimon, Kevin Warsh and Paul Ryan?—could get the ball rolling. Chuck Schumer, soon to be minority leader, could propose to John Thune, the presumptive majority leader, that each would work to enact commission recommendations. This would rescue a vital governmental program and remind the public of Democratic policies at their best.

The Democrats will have plenty to object to. Trump’s proposed tariffs and threatened mass deportations risk economic harm and national isolation; deportations in particular could deliver an economic shock, rapid reinflation, and fear and despair on the streets. To the extent that Trumpian isolationists prevail in foreign policy, Democrats will be a crucial voice reassuring allies that the U.S. will continue as the leader, and when necessary as the protector, of the free world.

But resist on the merits, not just because Trump is the one proposing. A good watchword: when a bad person does a good thing, it’s a good thing. Elon Musk, the business wunderkind-turned political loudmouth-turned Trump efficiency chief, has said he will recommend that Trump require federal employees to return to the office, rather than work at home. That strikes me as sensible and overdue. Save the criticism of Musk for the bad stuff, like when he called out by name as a symbol of waste a federal official whom he “knew” only from a mean-spirited tweet on X.

The thought of supporting even an occasional Trump policy will upset some Democrats, for whom resistance has become a badge of faith. But faith has been a poor guide to winning elections. Let the Republicans, fresh with their sweeping victory, be the party of absolutes, of ideological certainties and holy crusades. They have two years in which to make mistakes, and they will make plenty. If the Democrats step toward the center, make themselves a pragmatic and reasonable opposition, they will be waiting in the wings.

The NBER report on state's response to covid actually does have a party color to It's results. Published in the International Journal of the Economics of Business (paywall), but free here https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w29928/w29928.pdf.

There were six states that did not lock down with the rest of the country. All six had republican governors. A couple states, Utah and Florida, in relative quick fashion opened up as well. Those 8 states are all represented in the top 15, and 2 of which were ranked first and second. The result is clearer at the bottom of the ranking, with the worst ranked being New Jersey, DC, New York, New Mexico, California and Illinois.

In the Substack Silent Lunch, David Zweig concluded the best advice during covid was that if you felt sick, to stay at home. It seems all of our mother's from decades ago knew best.

I agree with a lot of the criticisms of the Democrats above - like most investors I am socially liberal but economically pro-market - but there's a danger we just project our own views on why Harris lost.

For example, I agree that Biden's climate policies probably costed Harris votes; but I honestly don't think that many voters in Blue Wall states switched parties because of the tax on buybacks.

Taking a leaf from our experience with Brexit in the UK, I would say that voters are far more driven by emotions than by economics, and we probably all have an in-built hostility to peopple who don't look and sound like us. America First is a simple, powerful political message.

The corollary is Democrats should start stealing tricks from the Trump/MAGA playbook. Every policy should be packaged as populist and pro-USA. And drop the identity politics stuff that cost votes.