Did the Federal Reserve cause the mess in Afghanistan?

Probably not. But America’s central bank is under siege for virtually everything else. And strangely, though this Fed is one of the most liberal in history, the heat is coming mostly from progressives.

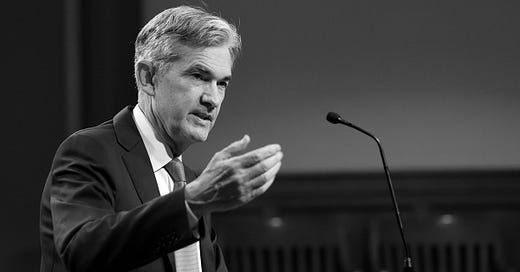

President Biden is being urged to sack Jay Powell, the Fed chairman, a Republican who was tapped by Donald Trump and whose four-year term expires in February. There is criticism of Powell from the right, over inflation, which has climbed to its highest level in 30 years.

But there is sharper criticism from the left. The Fed is being blamed for not being a tough-enough cop on the banking beat, for spurring income inequality, for failing to address racial disparities, even for being weak on climate change.

A visitor from Mars might wonder whether the Fed was some sort of omnibus agency for social and environmental welfare. It isn’t. And it can’t be.

Most of the criticism misconstrues the Fed’s purpose and how it operates, assuming that it necessarily tilts in favor of either rich or poor. In reality, the Fed’s job is to maximize sustainable growth across society as a whole, although to be sure, at any given moment not everyone will be prospering at the same rate.

The Fed has relatively few tools, and those it has are blunt. The primary instrument of monetary policy is the (overnight) Federal Funds Rate. The Fed cannot raise this rate on the rich while reducing it for the poor, nor on any social subgroup.

By contrast, Congress can target aid to students, farmers, or homeowners. It can address inequality by raising taxes on the rich. Similarly, the Environmental Protection Agency can implement rules that either favor business or protect water and air quality.

But consider Karen Petrou’s withering critique in the New York Times, “Only the Rich Could Love This Economy.” Ms. Petrou, managing partner of Federal Financial Analytics, a public policy firm, charged that the Fed’s “ultra, ultra low” interest rates have resulted in “wider wealth inequalities.”

It is true that ultra-low interest rates have encouraged investment and speculation in the stock market. They also have contributed to a booming, though still incomplete, resurgence in employment (16.7 million jobs recovered, which is three quarters of those that had been lost). The recovery in demand has spurred strong wage gains. It is hard to imagine that workers would prefer not to be employed just to see investors suffer.

The Fed is particularly ill-suited to address inequality because “inequality” is derived from two measures—income levels of the poor, and those of the rich—and each of those measures is multi-determinate. To move one lever up and hold the other flat or down requires serious fine-tuning for which Congress is better equipped. Even then, the causes of inequality remain uncertain.

Criticism from Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) has focused on the Fed’s role in regulating banks. Warren and other progressives have pressured Biden to replace Powell, who has indeed voted in favor of loosening various bank-safety rules designed after the 2008 financial collapse. During a Senate grilling of Powell in July, Warren chastised the chairman, asserting, “I see one move after another to weaken regulation over Wall Street banks.”

This assault on Powell misses the mark for two reasons. In the ways that matter, banks remain well-regulated. Capital rules have been relaxed—but not for the biggest banks. And for both the biggest banks and for the next tier of large banks, capital in proportion to assets remains at historically high levels.

Warren herself told Powell during the July hearing that banks are stronger than in 2008, but added, “That’s the wrong standard. The question is whether or not they are strong enough to withstand the next crisis.”

The evidence is reassuring. In an annual stress test, the Fed found that even during a severe recession, banks could continue lending to households and to businesses. Such forecasts are not perfect. But we have just experienced a severe economic crisis (the onset of the pandemic). Banks survived with flying colors. Despite the economic shock, no major bank failed, and none sought or received a bailout.

Moreover, Powell’s record as a deregulator is anything but one-sided. He acquiesced to banks on some items, not on others. He did not approve a sought-after change in assessing loans to low-income communities. He refused to ease the capital surcharge on the biggest banks. But he did make the stress tests, in some ways, less onerous.

Powell’s case-by-case approach gets to the second reason why the criticism fails. Progressives make it sound as though tougher rules are always better and that the Fed has sided with big banks and against the people.

In fact, regulation involves a tradeoff. Both banks and their customers (including the poor) benefit, in the short term, from more liberal rules, because they permit more lending. But overly loose rules lead to excessively risky lending, to the detriment of people and banks and to overall financial stability (read: 2008). The Fed’s supervisory assignment parallels its monetary role. It’s less about choosing sides than about encouraging growth while not permitting lending practices that jeopardize stability.

Peter Conti-Brown, a Wharton School associate professor and author of “The Power and Independence of the Federal Reserve,” says the criticism of Powell is rooted in his independence, which is seen as “a threat to more aggressive and ideological” approaches. He notes that the chairman, who is popular with members on the Hill from both parties, is a pragmatist “who views the Fed's monetary policy commitments to price stability and especially maximum employment as the bedrock of the central banker's role.”

Not everyone accepts the Powell definition of that role. Groups such as Americans for Financial Reform want the central bank to prioritize climate risk. Twenty-five House members, led by Mondaire Jones (D-N.Y.) and Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.), have called on the Fed to incorporate climate change, as well as the needs of communities of color, into monetary policy. The first would politicize the Fed in an area outside its competence; the second overlooks that the Fed is already vigorously pursuing full employment irrespective of color. As the Economist magazine observed, “there are limits to what monetary policy alone can achieve.”

In fact, Powell’s purposes are the ones assigned to the Fed by law.

Congress created the Fed, in 1913 after extensive study, “to furnish an elastic currency.” To the founders, “elastic” signified that the central bank would expand or contract the rate of money growth according to economic conditions. Their idea was to create a central “reserve” that would lend to banks in times of distress, to avert financial collapses, and contract the money supply to avoid inflation.

In 1978, Congress added the goal of full employment, specifying that the Fed should minimize the harmful toll of recessions. It defined the Fed’s inflation-fighting goal as “reasonable price stability.” The bill was coauthored by Sen. (and former Veep) Hubert Humphry (D-Minn.), a vigorous civil rights advocate. The legislation did not ignore the Fed’s role in racial progress. It wisely argued that “Increasing job opportunities and full employment would greatly contribute to the elimination of discrimination based upon sex, age, race, color, religion” and other such factors.

Biden should judge Powell on how he fulfills this mandate. The Powell Fed has earned an “A+” on dealing with recessions. And it deserves an “A-“ on full employment, having taken the jobless rate to 3.5%, its lowest in more than 50 years, before the pandemic struck. It is now 5.4% and falling.

Powell’s record on inflation is suspect—but the law says “reasonable,” and it can be argued that it was reasonable (or unavoidable) to raise inflation to engineer a recovery. History will judge Powell according to whether or not the inflation, currently 5.4%, persists and becomes a hinderance to growth.

In the meantime, the chairman has earned another term.