Policy and Tradeoffs

Exchanging Good for Bad, the Senate Botches Wall Street Taxes

Legislating in a democracy involves balancing plusses and minuses. As Abraham Lincoln, during his one term in Congress, said, “There are few things wholly evil, or wholly good. [i]

Policy involves tradeoffs. In their efforts to tax Wall Street, Democrats in the Senate came down on the wrong side of the tradeoff—not once but twice.

Up to the eleventh hour, the vaunted Inflation Reduction Act narrowed an unwarranted, and long-criticized, tax break for managers of private equity funds.

Then, Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.), demanded that the break be restored. In the past, Sinema has risibly asserted that in Arizona private equity supports more than 100,000 “workers and their families.”

It certainly supports the Sinema family. Investment firms, including KKR, a major private equity sponsor, have donated $2.2 million to her campaigns over the last five years. The industry has aggressively lobbied to keep the status quo—and it succeeded again.

When the Democrats caved to Sinema and allowed the tax break to stand, they sought to make up the lost revenue with a new, 1% tax on corporate share buybacks.

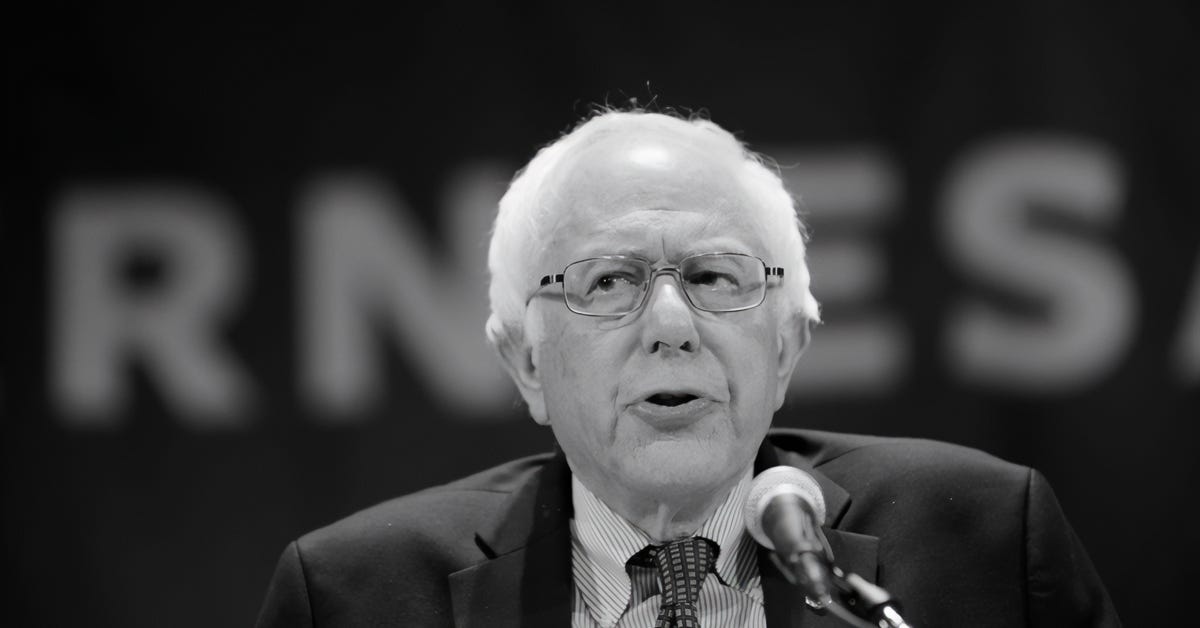

Penalizing share repurchases has been a persistent goal of progressives such as Bernie Sanders. The issue is red meat on the progressive stump. But the buyback tax will carry a large cost in wasted resources and less efficient capital markets.

Thus the perfectly botched tradeoff: the Senate killed a fair and necessary tax and replaced it with a punitive levy whose effects will be almost entirely negative.

Let’s look at private equity first. If you invest in a P/E fund, any profits are taxed at the capital gains rate, which is substantially lower than the rate on ordinary income. The rationale for the lower rate is to incentivize investment.

You could argue that, even so, capital gains rates should be higher, but no one disputes that the profits on capital gains (be it from private equity, or common stocks, or selling your stamp collection) should be treated as, indeed, a capital gain.

What’s at issue is the so-called “carried interest”—the fee that P/E fund managers deduct from the profits earned by their investors on their investors’ own capital. This fee, properly considered, is ordinary income yet it is taxed as a capital gain.

There is no justification for this break. I will not invest less money in a fund managed by KKR or Blackstone on account of the tax that is later imposed on the fee that KKR or Blackstone charges me. After I pay my fee, I couldn’t care less what happens to it.

The tax break does not create an incentive. It runs counter to the spirit of the distinction between ordinary income and capital gains, which is to lower the rate on capital. Since the tax in question is levied on managers, who did not put up the capital, the mangers do not deserve the break.

It should be clear that this unwarranted break goes to an elite group of the wealthiest people on Wall Street and in America. Eliminating it would have punished no capital and cost no jobs. Its preservation has been and remains a scandal.

It is unfortunate that the Senate sought to fill the revenue gap by taxing corporate buybacks. Buybacks are mirror images of processes that raise capital, such as IPOs. One is a corrective to the other. If you need capital, you sell stock. If you have an excess, you repurchase it. Each process works better thanks to the existence of the other.

New companies couldn’t get launched without capital, and that capital has to come from someplace. Buybacks are one way of transferring capital from firms with a surplus to firms with a deficit.

At some point, capital invested in typewriter companies was redeployed in IBM, and at some later point, capital in IBM went into Apple. This is a good thing.

Starving firms of capital would result, over time, in a less productive and less prosperous economy. Pressuring companies to retain a surplus of capital would have similar effect. Too much of any resource results in waste.

Consider an analogy to labor. Millions of workers migrate each year, generally for better jobs. Supposed we taxed anyone who left their state? It would slow the movement of people to firms that are willing and able to pay higher wages. It would be a dead anchor on growth.

Share buybacks are frequently demonized in two ways. One is the claim that they enable executive bonuses. I’ve written easily a score of columns on executive pay, every one of them quite critical.

But many things “enable” executive pay; in fact, everything a firm does to increase profits “enables” it to increase bonuses. If a firm invents a popular new product, bonuses will likely go up. Should we tax it for the crime of innovation?

If you want to reduce CEO pay, go after it. Require shareholder approval of executive pay packages (currently, say-on-pay votes are only advisory). Tax bonus and option income at higher rates. And I think there is strong case for tightly regulating CEO stock options (there is virtually none now) because the conflicts of interest are so great.

Progressive critics also say companies should use their capital to pay higher wages rather than “reward” shareholders. But that capital was invested by those shareholders to earn a return. If management cannot productively employ it, it has a duty to return it.

Moreover, assuming managers have an accurate grasp of their firms’ prospects, repurchases work in society’s interest. The selling shareholders in firm A will pay a tax, and then either spend the proceeds, goosing the economy, or, in most cases, reinvest in some firm B. That second firm’s workers, clients and networks will gain to the same extent that firm A has lost capital. The only difference is that firm A doesn’t want the capital, and firm B does.

The likely effect, particularly if the 1% tax is ever raised, will be wasteful misallocation of a scarce and precious resource: capital. In the long term, it will discourage companies from raising capital, due to the fear they will be stuck with it.

* * *

In a piece in last weekend’s Wall Street Journal, I recalled the seminal arguments of the economist Arthur Okun, who likened economic policies to “buckets.” Due to poorly designed incentives and other inefficiencies, policy buckets can spring “leaks” that squander some or most of the intended gains.

According to Okun, a former chief economic adviser to President Lyndon B. Johnson, the trick for policymakers is to design buckets with the smallest leaks—that is, the smallest negative side effects.

In Okun’s terms, the Senate struck out twice, nixing a bucket (the private equity tax) with virtually no leak, and enacting a buyback tax that is full of leaks.

Since reading Okun’s book, “Equality and Efficiency: The Big Tradeoff,” I have been thinking a lot about tradeoffs. As I wrote in The Journal:

“Once you start looking at the world through the lens of tradeoffs, policy debates become less about right and wrong and more matters of give and take. Covid lockdowns aren’t good or bad—they reduce the risk of illness but impose an economic and social cost. A gas tax holiday offers relief at the pump but encourages people to burn more oil.”

The job of policymakers is to get on the right side of tradeoffs, meaning, to get the most good with the least negative effect. You can read the full WSJ article on tradeoffs here.

[i] Collected Works of Lincoln, v 1, 484.

Preferential tax treatment of fee income is a very bad idea. Imagine for a moment if real estate agents were able to convince Congress that they, too, should receive similar tax treatment of their fee based income. Pretty soon, every fee based business would want the same break. The ensuing chaos and likely damage to our fiscal health would be enormous. The capital gains tax was intended to reward investors for their risk in making long term capital investments. The carried interest giveaway only benefits fund managers.

Well said Mr. Lowenstein, couldn't agree more!

If three guys own a small business and one of them decides he wants to cash out and sell his shares, and the remaining two owners offer to buy him out, should they be taxed for purchasing his shares? It makes no economic sense, but I suppose my first mistake was my illogical assumption that politicians would legislate tax laws that make economic sense.