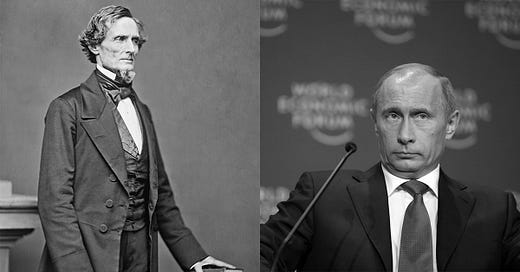

Vladimir Putin is making the same miscalculation that doomed Jefferson Davis's Confederacy a century and a half ago. The West can learn from it.

In 1860, the American South was the world’s largest producer of cotton, the essential raw material in textiles, the largest manufacturing industry. The Confederacy nourished a delusion that its vast cotton plantations would neutralize potential military threats. Today, Putin has counted on Russia’s energy supplies to minimize the West’s response to his invasion of the Ukraine.

The comparison may seem a stretch, but consider:

Russia supplies 55% of the gas and 45% of the oil to Germany, the largest economy in Europe. The American South produced three quarters of the world’s cotton, including to England, the world’s leading economy.

Putin reckoned that since Europe has a voracious appetite for energy, the West’s reaction to any military action would be muted. His reliance on a small circle of advisers apparently clouded his judgment.

The American South was a similarly cloistered cocoon. Slave labor was banned in the British empire and widely condemned, yet as the Civil War drew near, the South brimmed with overconfidence. In 1858, James Hammond, senator from South Carolina, boasted, “No power on earth dares to make war upon [the South]. Cotton is king.”

Two years later, after the election of Abraham Lincoln, South Carolina seceded. Observers wondered whether the cotton states had lost their collective heads. A dissenting unionist in Charleston opined that South Carolina “was too small for a republic but too large for an insane asylum.” Gen. William T. Sherman, who was stationed in Louisiana, said, “Men here have ceased to reason.”

The South had been conditioned to believe that its cotton—which provided jobs for hundreds of thousands of mill workers in England and France and in New England cities such as Lowell and Lynn—would make war untenable to the industrialized nations. Even after war was declared, LeRoy Pope Walker, Confederate Secretary of War, bragged that if any blood were shed, he could clean it with his handkerchief.

So deluded was the Confederacy that its leadership rejected the urgent suggestion of Judah Benjamin, the attorney general, to ship a sufficient cotton supply to England, while sea lanes remained open, to finance a potentially long war. Richmond expected a brief war and that, if need be, Britain and France would intervene to stop it.

As with Putin’s Russia, the Confederacy’s delusions had been nourished by years of relative isolation. It viewed the North as weak, riven by class conflict whereas the South had the supposed benefit of a harmonious labor system (slavery). The autocrat Putin similarly viewed the West as weak, vulnerable to the inevitable discord and inefficiencies of democracy.

Both overlooked that democratic governments have a strength unavailable to autocrats—the support of the people. Although the Confederacy was (for non-slaves) democratic in form, secession was not a popular movement. Three-quarters of southern whites did not own slaves and therefore had no economic interest in secession. Only one state, Texas, dared to submit secession to a popular referendum. The other Rebel States deliberately chose secession by convention, and the conventions were stacked with wealthy planters.

The planters’ fatal miscalculation was that England and France could not survive without their cotton. Although they did suffer mass unemployment, slowly, Europe was able to procure new supplies from Egypt, India and other producers.

Meanwhile, the Union naval blockade constricted and shut down Confederate trade in cotton, arms and everything else. Economically, the Confederacy was strangled. The armies fought on, but popular support flagged. The first sign that the Confederacy was in trouble were the bread riots in Richmond and in other cities.

As its economic desperation intensified, inflation reached epidemic proportions and people went hungry. Factories could not obtain spare parts and desertion thinned the ranks of Rebel armies. A Confederate leader aptly summarized, “The Yankees did not whip us in the field. We were whipped in the Treasury Department.”

Putin is being whipped in the Treasury Department too. Even if his troops eventually occupy Kyiv, Russia is cut off from the world economy—not by torpedoes but by banks and computers. If western sanctions remain in place, the suffering of ordinary (and innocent) Russians will intensify.

During the American Civil War, the Lincoln government erred by approving a complicated system of licenses that permitted supposedly loyal traders to bring cotton out of the South. This furnished a vital lifeline to Richmond, even if the revenue was only a tiny fraction of the prewar total. General Sherman, horrified by the rampant commerce across military lines in the environs of Memphis, grasped the essential truth: “We cannot carry on war & trade with a people at the same time.”

The West (and not just the U.S.) should learn from this mistake and impose a total ban on Russian energy products. Even if Ukraine cannot win the shooting war, an economic depression would unmask the Russian regime in the eyes of its people. History suggests that that will hasten an end to Putin’s self-deluded war.

Roger Lowenstein’s new book, Ways and Means: Lincoln and His Cabinet and the Financing of the Civil War, was published this week.

Interesting historical parallel and perspective. I wonder about the change in global markets in past 160 year, however, and how possible an oil embargo of Russia is.

I'd like to add that I only just found this blog. But I've read everything you've written since you were a columnist at the WSJ. I just re-read your Buffett biography for the first time in 25 years. When I opened it, I found a couple fan letters I'd sent you, thanking you for helping set me on a good direction with investing. Now retired, I'm all the more grateful to you.

Ben K

Dear Roger Lowenstein,

Thank you very much for your extensive article on Russian oil and it's impact on geopolitics. Please accept my sincerest appreciation of your offer to help and the time you dedicated.

Thank you for your kindness,

David M