Maine has more coastline than California and fewer people than Connecticut. Right there, that should tell you it’s going to have a surfeit of tourists and not enough people to wait on them.

But post-pandemic is something else. Home Kitchen Cafe — a favorite breakfast and lunch spot in Rockland — is advertising for line cooks, bakers, dishwashers, servers, you name it.

The Luke's Lobster in Tenants Harbor, a summer favorite, failed to open. Restaurants that did open are absurdly crowded.

Up in Blue Hill, my wife called 34 times to order a “caramey” (pizza with caramelized onions). Another diner, who must have really wanted pizza, called 151 times.

The summer of 2021 has dawned on the strangest economic problem of our lifetimes: that of the missing worker. It’s a national phenomenon, nowhere more acute than in the Pine Tree State. Where did the workers go?

Not Enough Mainers

Maine used to have a thriving paper and pulp industry. Like manufacturing across the country, it’s a shadow of its former self.

Many of its former mill workers were never retrained, and simply dropped out of the work force. As manufacturing declined, various indicators of social dysfunction, including depression, suicide, opioids- and alcohol-related deaths, skyrocketed. Rural counties became highly dependent on social services.

Tourists visiting galleries and antique shops may not notice these dropped-out workers in the rocky seaside villages like the one where we have a second home. But they are here.

The problem of the white male worker, the problem of his disaffection, has been the political story of the decade. In Maine, it is the story, because Maine is the whitest state in the nation (less than 2% is African-American).

Maine is also the oldest state, with a median age of 44.7 compared to 38 nationwide. A high school principal in far northern Aroostook County, famed for its potatoes, once joked that their biggest export crop was the top third of the senior class. Yes, Maine leads the nation in lobster production. But what its lobstermen earn in a year, Nevada casinos gross every ten days. It isn’t enough. So the young aren’t staying.

The mystery is, jobs are going unfilled. Signs offering higher wages and signing bonuses line the eateries along Route 1. As one former food service worker explained, sort of, to the Bangor Daily News, “Restaurants are a grind.”

This summer, the state offered a $1,500 bonus to people on unemployment who returned to work. It got few takers. Other programs seek to lure vacationers and others into moving here. The problem remains — really two problems.

First, Maine has a people shortage. At 43 people per square mile, it’s only half as dense as the U.S. overall. Neighboring New Hampshire is three-and-a-half times denser. Even Colorado is denser than Maine. (Judged from the Census tables, Maine can seem hardly a part of New England at all. Its median household income ranks 36th, ahead of a cluster of southern states. It ranks below average in poverty, health insurance coverage, and disability recipients, but ahead in high school graduations and Covid-19 vaccinations.)

Not surprisingly for an older state, deaths outnumber births. Its population is growing (just barely) thanks to a trickle of immigrants. But it’s truly a trickle: only 4% of Mainers were born outside the U.S. In the country as a whole, 14% were.

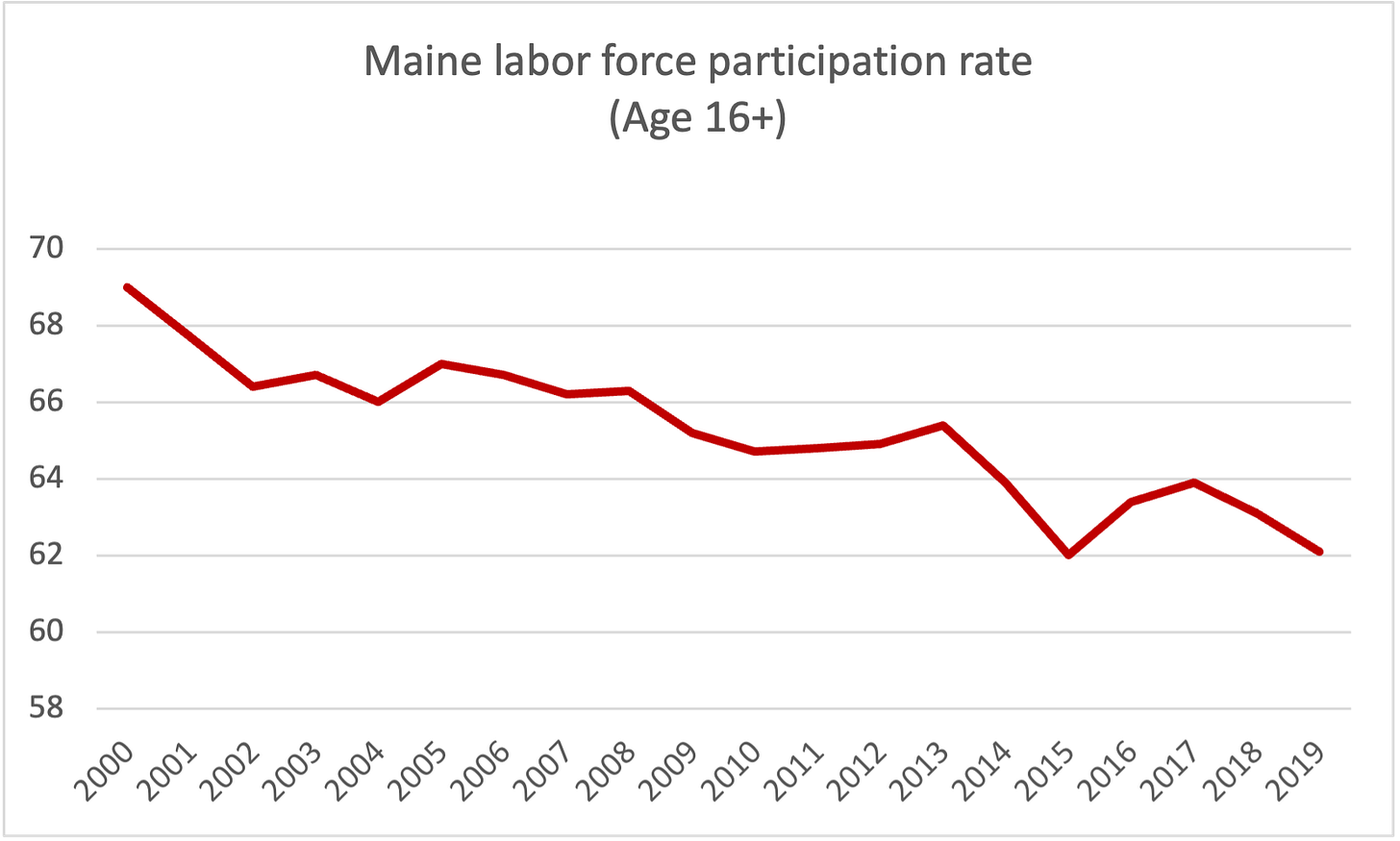

The other significant issue is labor force participation, that is, the percentage of those who are here working or looking for work. In 2000, 69% of Mainers 16 and older were in the labor force. Now, only 62% are, a stunning drop. Maine was hit hard by the pandemic, due to its high proportion of tourism workers. But that’s almost besides the point. As John Dorrer, a retired labor economist in Maine, says, the problem is long-term, and structural.

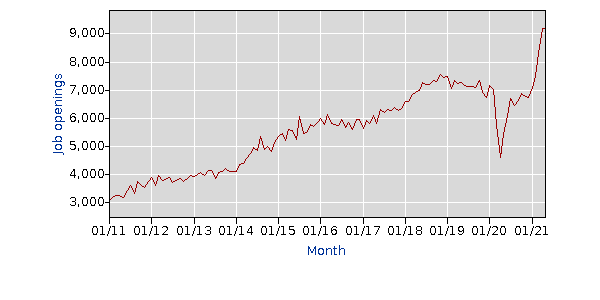

In many ways, the rest of the U.S. is better off. It has higher population growth, more immigrant men (who work at higher rates), more skilled workers. But if you look at the direction of the U.S. labor market, not so much. Even with the number of jobs down by 7 million from the pre-pandemic peak, the number of unfilled jobs is at an all-time high.

Job Vacancies Soar

Explanations range from post-covid epiphanies (work is a grind) to reluctance to leave the home to the disincentive of federal unemployment insurance. But these, too, are beside the point.

Consider the shouted news from Jim Glassman, head economist, commercial banking, J.P. Morgan: “Help Wanted: Why the U.S. Has Millions of Unfilled Jobs.” Glassman cited a skills gap, the manufacturing decline, baby boomers’ retiring. He didn’t mention the pandemic, because he wrote that just before its onset. The pandemic re-set most labor market indicators, but it didn’t interrupt long-running trends.

Demographic headwinds have been detectable for years. The Congressional Budget Office warned in 2011 that a labor force slowdown could threaten growth. Immigration papered it over, or allowed economists to ignore it.

But over recent decades, the number of new workers entering the labor force plunged from 200,000 a month to merely 65,000 a month. The causes included not only retiring boomers but a declining birth rate, a leveling of legal immigration and a decline in undocumented workers. Julia Coronado, founder of MacroPolicy Perspectives, recently said that future population trends could look more like those of Europe and Japan. She concluded drearily, “Demographics is destiny.”

The Missing U.S. Worker

Slowing demographics also have positive effects, namely higher wages. But the slowdown in the labor force isn’t all about aging. Even among men under age 55 the participation rate is falling. And it has been for decades. “Why it is falling is a big mystery,” says Michael R. Strain, an economist at American Enterprise Institute. “It’s been happening so long that any one explanation is surely incomplete.”

No doubt, the U.S. is suffering a case of Maine — lack of the right skill mix, social dysfunction, declining birth rates. One lesson of the post-pandemic boom is that the U.S. needs better education and job training, and more effective social services. And while you wait on line for that lobster roll, it’s worth considering that — far from being unAmerican — immigration remains the vital secret sauce of American dynamism.

Many of the hotels, inns and restaurants are open seasonally for 4-7 months. The only readily available workforce are teachers, students and ski instructors. The available workers in prior years were temporary visa visitors from western and Central Europe. The US needs to welcome those people again. For full time working Mainers, they need construction jobs and supply-chain professionals since Maine enjoys quicker travel and communication with western Europe.

I've spent a lot of time in Maine, starting in the late Eighties. I've watched it go from a quirky, fiercely independent vibe, where people were perhaps a little on the poor side, but took care of their own lives and communities, to a sad, dispirited welfare state. There was a wholesale embrace of state dependency by their politicians during the last thirty years (Chellie Pingree is their Patron Saint), and now Mainers have become a sad lot--more's the pity, for they enjoy unbelievable natural advantages: the beautiful and varied geography, low density, etc. But everywhere, there is the stifling public sector, even in the tiniest hamlets. When "working for the town" is the highest aspirational career achievement, you've got a BIG problem...