These Two Gentleman Love Tariffs

These Economists Were Free Traders

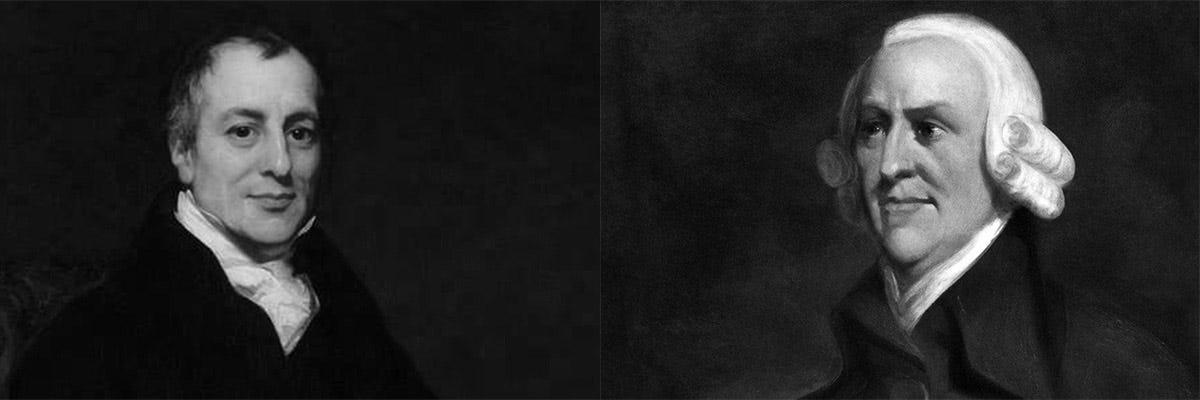

David Ricardo (left), and Adam Smith,

Donald Trump’s anointment of J.D. Vance, a fellow ideologue now his veep nominee and intellectual Sancho Panza, confirms that, if elected, Trump’s signature economic policy will continue through the next four years and conceivably beyond.

This is the policy that most defines Trump and that represents his greatest potential for economic harm. Not his tax cuts—whatever you think of them, taxes have always fluctuated and Trump’s cuts were nothing new.

The policy that will mark the Trump era in the history books is protectionism—a 180-degree pivot from seven decades of postwar, bipartisan support for free trade.

Trump’s venom for trade, a staple of his naïve fantasy to remake America as he imagines it used to be, is a bedrock belief. It’s one of few issues on which he has been consistent (something that cannot be said for his views on abortion, entitlements, or any number of others).

And it’s emblematic of his larger nationalism—his wish to fence in America and make it, like Trump himself, suspicious, hostile, and defensive. It expresses his essential pessimism, which darkens his view even of market competition and private enterprise. Better to let the economic commissar in the red necktie decide which products Americans can buy from whom: Don’t leave it to private businesses or consumers, that is, to the American people.

J.D. Vance has Trump’s populist, neo-interventionist instincts. If Mike Pence’s nomination in 2016 represented a ransom check to evangelist Republicans, Vance signals the former President’s wish to solidify and extend tariff policy and his (similarly harmful) anti-immigrant nativism.

In some ways, Vance is more Trump than Trump. As an economic populist, he is openly skeptical of business and an admirer of Lina Khan, President Biden’s FTC chairwoman, known for creative theories of antitrust and, so far, mostly losing litigation.

But Vance is a newcomer to protectionism. In Hillbilly Elegy, his 2016 memoir of growing up poor in Appalachia, the book that made him known, he recounted the widespread unease of folks in Middletown, Ohio—Vance’s hometown—when Kawasaki, a Japanese firm, bought a controlling share of Armco, a steel company. After the furor abated, Vance’s grandfather, who had worked at the steel plant, told him, “The Japanese are our friends now.” As Vance wrote, “If companies like Armco were going to survive, they would have to retool. Kawasaki gave Armco a chance.” In the interconnected global economy, cutting off capital from a foreign source would be self-destructive, as the Yale Law grad had come to understand.

Or had he? By the time Vance started running for the Senate in 2021, the Japanese were not “our friends”—or not his friends, even though they remain staunch American allies. In a replay of the Armco purchase, late last year Nippon Steel won a bidding war to purchase the foundering U.S. Steel. The deal was clearly in the workers’ and in the U.S.’s interest. Nippon offered twice as much as a domestic competitor and promised to inject needed capital and technology to make U.S. steel more competitive. It also promised to keep making steel in the U.S. and to keep the local headquarters in Pittsburgh.

Vance urged Washington to block the deal, in which, he claimed with rabid incoherence, “a critical piece of America’s defense industrial base was auctioned off to foreigners for cash.” Since his moonlight conversion, the former venture capitalist has been the most reliable of Trump’s trade hawks, with the possible exception of Peter Navarro, the resident anti-trade apostle when Trump was in the White House, who has been sketching a tougher anti-trade agenda for a possible second term while, in fact, serving a four-month jail sentence for contempt of Congress.

It brings me no joy to observe that President Biden, with a similarly wrongheaded show of empty patriotism, has also opposed the still-pending Nippon deal. Indeed, he has imitated his predecessor’s anti-trade policies, by sustaining some of his tariffs and requiring domestic content in federal projects, more than any Democrat in memory. Douglas Irwin, author of the opus, Clashing Over Commerce: A History of U.S. Trade Policy, told me, “The two parties seem to have converged.”

I have written about Biden’s protectionism before; this is Trump’s moment. But two distinctions should be made. First, Trump’s tariffs were of far greater magnitude. Trump’s first-term tariff hikes on steel, aluminum, solar panels, washing machines and other goods hit $400 billion in imports; Biden’s tariffs on Chinese semiconductors, electric vehicles and other goods affected $18 billion. And Trump’s proposals for a second term are of an order of magnitude larger.

Second, for Trump, who prides himself on being “Tariff man,” protectionism fits organically within his America First agenda, of a piece with his reluctance (at best) to aid Ukraine, which is unmentioned in his platform, and his growth-killing threat to deport “millions” of migrants, and his general hostility to multilateralism. Biden’s economic populism attempts to curry some of the same political favor, but he is no America Firster. He fully embraces the globalism that America and its allies institutionalized in the embers of the Second World War. The idea then and since was that global economic cooperation, including trade, was the surest vaccine against global depression—which in turn would be the surest defense against World War 3.0. As the famed professor of foreign relations at Cornell University, Walter LaFeber, used to say from a rather imposing lectern, military lines follow trade lines. It is almost a joke—it is a joke--that the 2024 Republican Platform mourns that the U.S. is in decline relative to the era when it “vanquished Nazism and Fascism” due to “unfair Trade Deals and a blind faith in the siren song of globalism.”

It was just such an anti-globalist mindset, evidenced in the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, and in retaliatory tariffs by other nations, that helped to extend the Great Depression, and that encouraged democratic governments to ignore the growing Nazi threat.

The theory of free trade is actually much older—dating to Adam Smith and David Ricardo—and it is one that any child could understand. Free trade broadens the pool of goods so that the best and cheapest products are more available to all. It would not make sense to force people in Wyoming to grow their own sugar cane or folks in the Mississippi Delta to raise their own beef—better to let each region specialize on their particular advantage or skill. Indeed, had tariff walls been erected between the states in 1789, each state now would be immeasurably poorer.

The same dynamic holds internationally—we sell wheat to the world and buy French wine, Korean appliances, Vietnamese textiles. Even in industries in which the U.S. is well-represented, such as autos, foreign competition is a vital check on quality and price. You don’t have to be as old as Biden or Trump to remember the pre-import days when Detroit gouged the public on overpriced clunkers. The special case of security threats posed by adversaries (China today) was recognized by Adam Smith, who, in The Wealth of Nations, defended an act to compel the use of British merchant ships (which could be commandeered by the navy in time of war) because, as he noted, “defence … is of much more importance than opulence.” But the portion of trade that poses a security threat, then or now, is slim, certainly less frequent than Presidents or Prime Ministers allege.

Mostly, the argument against trade is economic, and it doesn’t hold water. According to Gary C. Hufbauer, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, America’s engagement with the world economy since 1950 has produced cumulative gains that in 2022 boosted the GDP by 10 percent, about $7,800 per person or $19,500 per household.

To be sure, imports have cost the country jobs, an estimated 300,000 per year. That sounds like a lot, but 50 million people change jobs every year, fewer than 1% because their job was exported to China or elsewhere. Many more jobs are lost due to the relentless capitalistic processes of firms moving, or reducing output or going under, or innovating in ways that render some positions obsolete, including automation and improvements to efficiency (which is occurring in factories around the world, not just in the U.S.). The remedy for people victimized by such losses is to retrain them to work in growing, largely high-tech industries in which the U.S. is leading, artificial intelligence among them, not to prop up remnant factories in shrinking industries. One day this will be obvious. As Irwin notes, most millennials do not listen to Springsteen and they have never been inside a steel mill.

The benefits from trade are frequently said to favor elites, but the benefits of lower prices accord disproportionately to people of lesser means. Elites do not shop at Walmart. To people on a budget—some of them may live in Middletown, Oh.—a $4 blouse makes a big difference.

Trade also delivers tremendous benefits to exporters. But you can’t have exports without imports. If Americans didn’t spend overseas, other nations wouldn’t have the dollars, or the political will, to buy our products.

This was seen during the Trump administration, when the E.U., Mexico, Canada, India, China and others slapped retaliatory tariffs that cut into U.S. exports. Agriculture was a particular loser. Farm exports to China plunged by $10 billion, or nearly two thirds, in a single year. Soybean farmers and whiskey distillers suffered and bankruptcies in the farm belt hit a decade-long high. The Administration responded with $23 billion in welfare checks to farmers (responding to a crisis of its own making). This is the crazy illogic of tariffs: the government restricts imports of superior or more affordable foreign goods and punishes the industries in which America is most competitive.

Moreover, though Trump protected a few jobs in steel, downstream firms that use steel (and employ many more workers) suffered. On a net basis no jobs were saved; possibly some were lost. Meanwhile, the trade deficit increased.

If you want more of that, Trump/Vance is your ticket. Trump has floated plans for a 10% across the board tariff hike on most imports (from everywhere) and a 60% levy on China. This would amount to an estimated ten-fold increase in trade taxes. Trump has suggested he could then dispense with income taxes—also a fantasy. It would require a 60% tariff on every import to make up for income taxes (the total of imports is $3.83 trillion, while the U.S. collects $2.28 trillion in income taxes)—but of course, such a tariff (or anything close) would cause prices to soar, sales to plunge, and importers to look for other work. The sure result would be inflation and a serious economic dislocation or worse. This is the kind of protection that neither American businesses nor workers need. Given its basis in a fundamental misconception of trade as a zero-sum exercise instead of, like most free market transactions, one that produces net gains, it would push America into a darker future—not an imagined idyllic past, but a fearful constricted present.

We want “fair trade”. Reciprocal tariffs until removed, then “free” trade until “the cows come home”.

Always grateful for Roger's good sense and ability to illuminate financial issues.

I sent this column to a couple conservative friends, both who came out of the traditional Republican mode but have voted for Trump and will again. I was curious how they'd react on a topic I felt they'd be sympathetic to.

Their responses were very similar. Here's one: "In a nutshell, definitely gets to the heart of my issue. I do have trouble reading any of these articles on either side that go to such great lengths to inject just political oration. I would love a good article on the topic that is just based on the facts and well informed opinions without the political hyperbole."

I didn't feel Roger used any "political hyperbole." But this is how it landed on them. So, I wonder how this same column might be turned a little to be more persuasive with Republicans such as they.