In his recent testimony to Congress, Jay Powell admitted to misgauging the supply-chain problems caused by the pandemic.

“What we missed about inflation was we didn’t predict the supply-side problems, and those are highly unusual and very difficult … hard to predict.”

Kudos to the Fed chairman for admitting error. But has he recognized a more salient mistake?

Powell and other economists who have repeatedly undershot the inflation have treated rising prices as a supply-chain issue. Production delays and clogged ports mean fewer goods available for purchase. And the worldwide shutdowns caused by Covid-19 caused an unparalleled break in supply.

But this explanation misses an alternate contributor to inflation that is rapidly becoming as or more important: galloping consumer demand.

At first glance, the distinction might seem trivial. Whether too little supply or too much demand, the immediate result is the same: higher prices.

But the distinction matters. Supply issues are somebody else’s problem, i.e., not the fault of central bankers. And they can be wished away by the pleasant belief that sooner or later, supplies will revert to “normal.”

Overheated demand is a monetary phenomenon; it’s the result of too much money creation. And the evidence is accelerating that, as The Economist magazine stated, “America is seeing an unusual surge in demand, not just constrained supply.”

Prices are surging not just for automobiles or other products interrupted by the pandemic. They are rising smartly for rent, clothing, transport, and fast-food. The Cleveland Fed calculates a monthly inflation index stripped of items at either extreme (either very fast risers or very slow ones); that surged this fall to an annual rate of 4.55%, double its pre-pandemic rate. All prices rose in November by 0.8% — an annualized rate of 10%.

Incredibly, the Fed is still buying $90 billion of assets, mostly government bonds, a month. Every bond it acquires, according to the Fed’s own theory, stimulates demand.

The Fed may well “taper” the rate of asset purchases at this week’s Federal Open Market Committee meeting. But will it act with the requisite boldness? Overnight interest rates remain close to zero, a highly stimulative level.

Prolonged low rates did not lead to inflation following the 2008 financial crisis, because household balance sheets had been devastated by shaky mortgages and other credit excesses. Despite low interest rates, borrowing and therefore money creation remained quiescent, and the recovery was slow.

But the economic meltdown of 2020 was not primarily financial, and its lingering effects on the consumer were milder. The Fed was right to sharply cut rates when the pandemic hit and the economy plunged into freefall, but that ended in April 2020. Since then, growth has been vigorous.

Once growth resumed, the approach honed during the mortgage crisis no longer fit. And since the stimulus provided by Congress has been far larger than after the financial crisis, the Fed’s policy this time is adding fuel to an already hot fire.

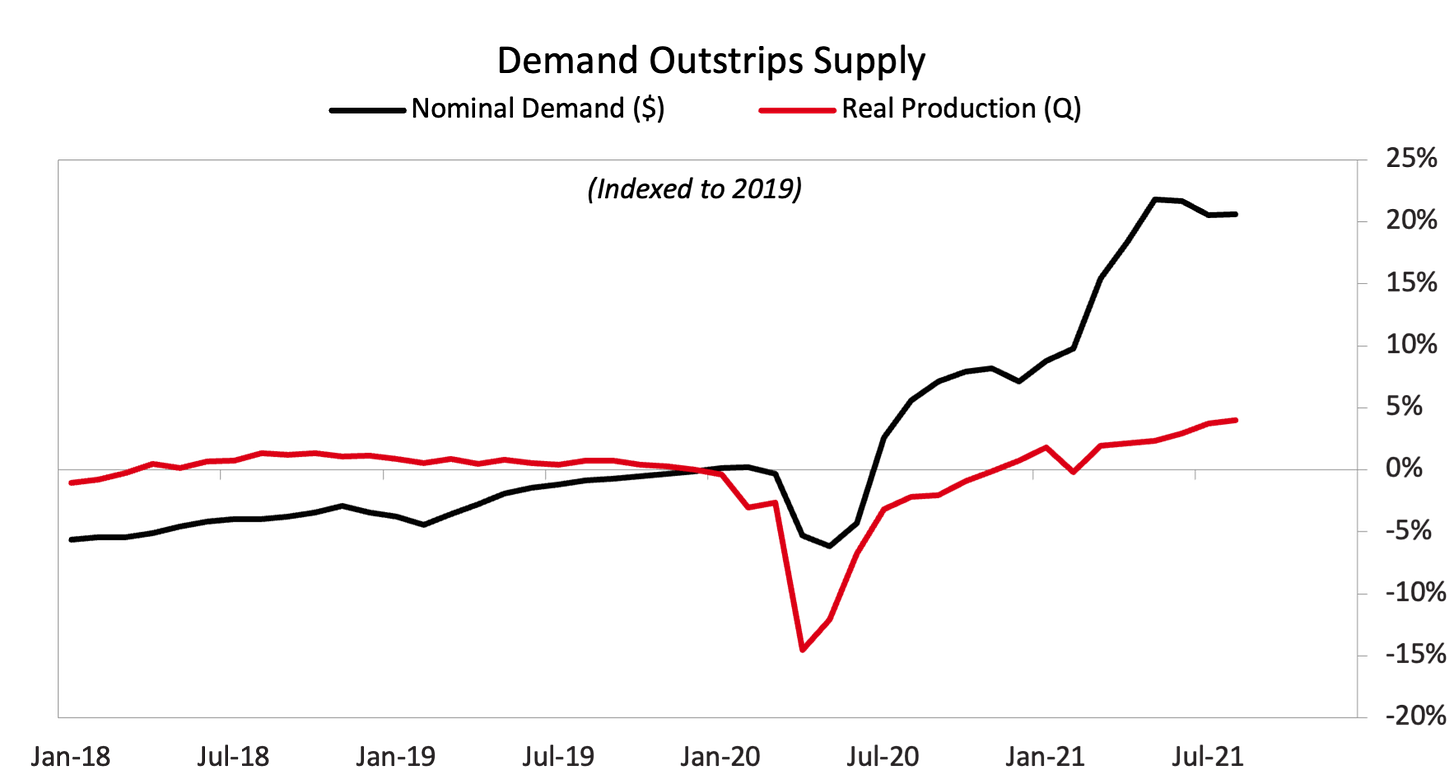

Fed policy now is stimulating credit, and credit leads to demand. According to a Bridgewater Associates research effort, bearing the dispositive title, “It’s Mostly a Demand Shock, Not a Supply Shock,” spending on goods has surged. Production has also increased, but hasn’t kept up. Prices, according to the firm, are ultimately driven by the amount of nominal spending relative to real production, and as the graph above illustrates, the two are out of whack.

In monetary terms, overheated demand and interrupted supplies will each lead to too much money chasing the available goods. But even were the problem wholly one of supply, which it is not, sooner or later the Fed would have to cool demand to conform to the quantity of goods on the shelves.

Alas, the obsession with supply-chain issues has fostered a hope that, if not this quarter then the next one or … maybe the one after … the economy will revert to normal. This overlooks how profoundly the pandemic has changed behavior, in ways that defy anyone’s ability to predict.

The tendency to treat the recent past as normal is irreducibly human. But normal is always in a state of flux—and following the pandemic it is changing faster than usually.

The Fed has leaned on the belief that once America’s missing workers return to their jobs, pressure on wages will moderate. But with employment levels 4 million shy of where they were, workers are not returning, or not in numbers great enough to fill the demand. Meanwhile, private sector wages rose in the third quarter at an annualized rate of 6.5%. And there is growing evidence of a vicious feedback loop, in which employees demand and receive higher wages that cycle into higher prices.

The Fed must react to the facts it sees, not to a hoped-for realignment to the status quo ante Covid-19. If future events demonstrate that it tightened policy too much, it can ease again. But with rates near zero, the risk of policy error is strongly on the side of being too dovish, i.e., stimulative. Even if inflation were to fall in half overnight, the short-term interest rate would still be far below “normal.”

It is said that the Fed cannot yet raise rates, because its past guidance precluded rate hikes until its bond buying was finished. But that guidance was based on the belief, now discarded by the Fed, that inflation was transitory. Better that it should admit an error than continue it. The time to begin to move interest rates toward a normal footing is now.

Pre-Order Ways and Means

My new book, Ways and Means: Lincoln and His Cabinet and the Financing of the Civil War, will be published by Penguin Press in March 2022.

You can preorder Ways and Means here: