Why Inflation Matters

The progressive myth of a "good" Fed

Jay Powell just finished his best year yet.

Caught flat-footed by accelerating inflation, the Federal Reserve chairman raised interest rates seven times by a total of 4.25 percentage points.

It was one of the swiftest rises ever. It killed the stock market and it may yet kill the economic recovery. Even as inflation moderates, Fed officials insist there will be no letting up on high—and higher—interest rates until the labor market cools. That means slower wage growth.

It may sound strange to celebrate a slowing economy and labor market, not to mention a bear market in the almighty Dow Jones.

And Powell has faced plenty of criticism. More than a year ago, correctly anticipating that Powell would raise the Fed Funds rate, then close to zero, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Ma.) called him a “dangerous man.” But the danger came from accelerating inflation. Powell would have been truly dangerous had he not acted.

This is a good time to remind ourselves why inflation matters. Outside of recessions, there are only a few periods in postwar history when workers suffered declining real wages. All of them were periods of high inflation.

During the 1970s and ‘80s, a period known as the Great Inflation, workers’ living standards repeatedly declined. Thus, consumer prices grew faster than wages from 1973 until 1976—a period encompassing the Arab oil embargo and an overly accommodative Federal Reserve—and again from 1979 to 1981, when the Iranian Revolution sent oil prices soaring once more.

During the 1980s, inflation moderated but remained high, on average about 5%. And as economist Michael Strain of the American Enterprise Institute has pointed out, “Real wages for typical workers continued to decline throughout the 1980s.” By the end of that decade, real wages had fallen 9% from 17 years earlier. That’s a brutal and sustained decline.

Since then, until the pandemic, wages almost consistently rose faster than the cost of living. Not coincidentally, inflation in the last three decades was low and trending lower. Workers’ gains especially outpaced inflation in the few years prior to the pandemic.

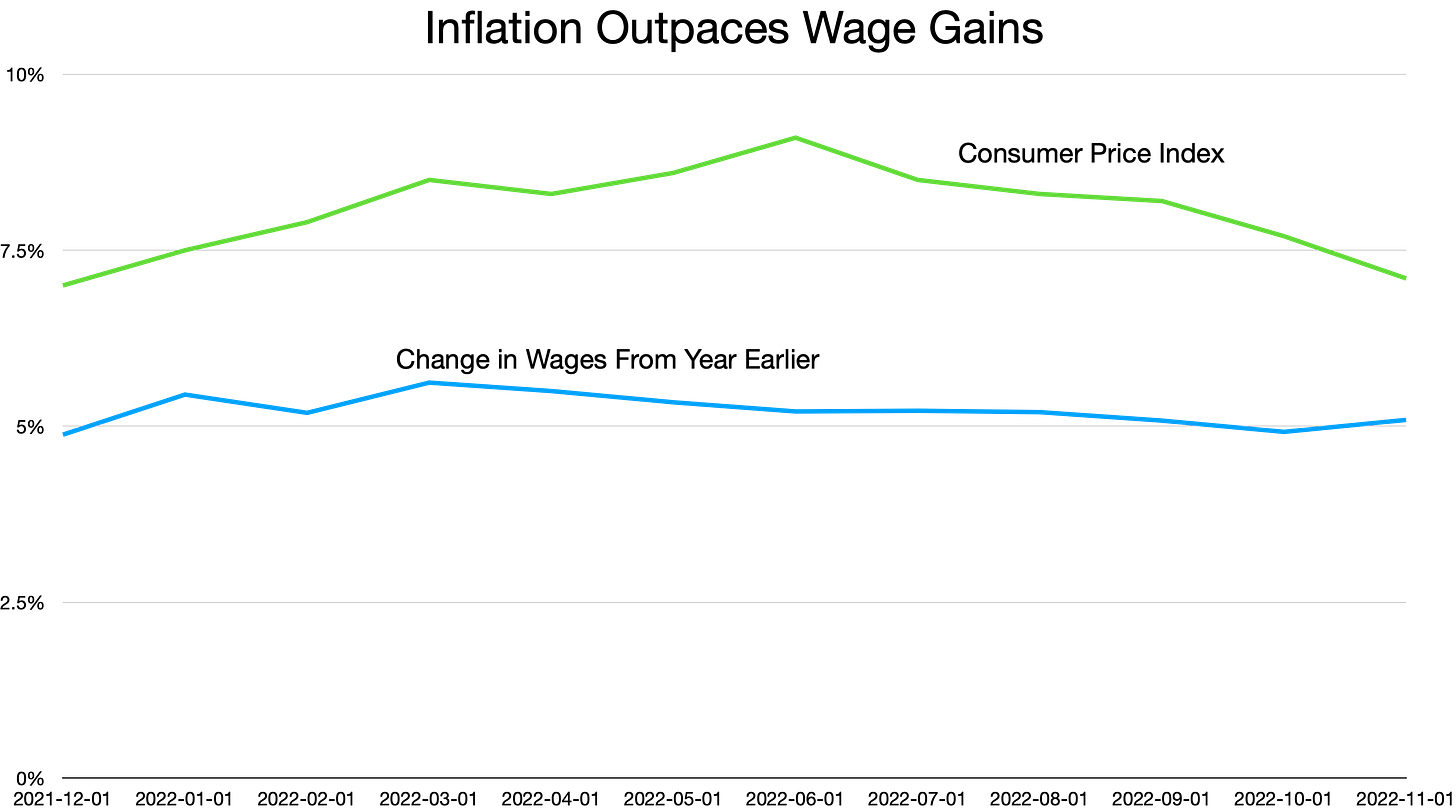

But not now. In 2022 (and for most of the preceding year), despite the hottest labor market in memory, wages have failed to keep up with prices. In November, although wages rose to a hefty 5.1% higher than a year earlier, consumer prices were 7.1% higher. In December, wage gains fell further (the December inflation number is expected this week.) The bottom line is that even with the unemployment rate at historic lows, currently 3.5%, workers are falling behind.

The only good news is that as inflation has moderated, the gap between inflation and wages has contracted. If the Fed can squeeze the inflation number back to its target of 2%, workers should start to receive higher paychecks in real terms.

The lesson is that low and stable inflation is neither pro-business nor (as some progressives maintain) anti-worker. High inflation is the enemy of just about anyone, save for debtors and stock market traders.

In short, there is no such thing as a Fed that is good for business but bad for workers, or vice versa. The only “good” Fed is that one promotes sustainable growth. Galloping inflation is never sustainable; rapidly rising prices are the antithesis of stability.

People unhappy that the Fed Funds rate has risen to 4.5% should consider some history. In the earlier inflationary episode, after a recession in 1974 the Fed mistakenly relaxed. Inflation came roaring back, worse than ever. In 1981, a new Fed chairman, Paul Volcker, had to raise rates to 19%. Now that was painful.

Jay Powell made one serious mistake, failing to recognize inflation for far too long. Now that the Fed has corrected course, he is dead right to insist that the Fed remain vigilant until the expectation of rapidly rising prices is quenched.

With Congress failing to exercise budget discipline, and the lower branch of Congress all but ungovernable, the burden of taming inflation will fall entirely on the Fed. It will take time, and some courage. Powell is on the right track.

Of all who are at fault for high inflation rates, the fed is the only one to admit their role and correct course. Hats off to them.

You are right - the preternaturally cautious Jerome Powell made a whopper when he told markets in 2021 that he foresaw no rate hikes through 2024. There is no reason for a Fed chief ever to make a statement like that, especially when the economy is projected to grow 6.5%.

He has been clawing back credibility ever since. He seems to have learned that Fed communications is not meant to inform; it is meant to support policy objectives. That is why markets are paying more attention to flattening numbers for inflation than they are to hawkish Fed statements.